Demian Johnson knows he has to be extremely cautious when he’s around his fiancée. He can briefly hug her when she arrives and maybe give a short kiss before she leaves. Sometimes, he can hold her hand, but they can’t have any other physical contact.

Johnson is 51 years old and is currently incarcerated at Mule Creek State Prison, a men’s correctional facility in Ione, a small city in Amador County, two hours east of Oakland. His fiancée, Hilda Wade, a retired home health aide, tries to visit him every Saturday and occasionally stays overnight in a nearby hotel when she doesn’t want to do the ninety-minute drive to and from her Oakley home twice in one day.

Wade told me in a phone interview that they are careful not to break any rules when they talk in the waiting room of the overcrowded prison, which currently houses roughly 2,800 prisoners in a facility designed for 1,700 inmates. “We’re very respectful in there,” she said. “We don’t want him to get no write-ups.”

Wade and Johnson started dating in the summer of 2014. One of Wade’s friends, who is engaged to a fellow inmate of Johnson, suggested the two meet at Mule Creek. When Wade’s friend originally asked Wade to come with her to prison to meet Johnson, Wade scoffed. “I don’t want to be with no guy in jail!” she recalled, with a laugh.

But her friend spoke very highly of Johnson, and eventually Wade decided she would tag along. The connection between the two was strong from the beginning, Wade said. “When I first met him, it was like I’ve been knowing him for years. It was like this instant attraction.”

After regular visits, it became clear to Wade that she wanted to marry him — once he is finally released. “He is the best man I’ve ever met in my lifetime,” she said. “I love him to death.”

Johnson told me in a recent phone interview from prison that their time together means the world to him. “Whenever I get a visit,” he said, “it’s the closest I get to feeling free.”

After she got to know Johnson, Wade figured he would be released soon enough given his extensive progress and long list of accomplishments during the 33 years he has spent behind bars. Johnson has worked as a program office clerk, a chapel clerk, a law library clerk, and a tutor. He has received his GED and certificates in electrical works, paralegal studies, vocational screen-printing, and office services. Johnson also co-founded and ran a diversion and education group for convicts and has counseled at-risk youth inside prison as part of a program that was featured on an MTV show. He has completed a victim awareness class, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, anger management and stress management courses, criminal behavior therapy groups, and many other self-help classes.

Additionally, Johnson has solid plans for his life after incarceration, including a standing job offer at a cleaning company in the East Bay and an acceptance letter from an Oakland-based program called Men of Valor, which provides transitional housing and other support services for people reentering society. He has several backup housing options and official letters of support from relatives and community members who have praised him extensively and written about the ways in which they would help him during the transition.

In short, Johnson’s prison case file shows that he has come a long way from the reckless eighteen-year-old boy who was arrested for murder on a rainy night in October 1982. Johnson, along with two teenage friends, who were drunk at the time, hopped in a cab in downtown Oakland to get back to his home in East Oakland, not far from the Coliseum. Their plan was to jump out of the cab before paying, according to Johnson’s later testimony. But just as they were getting ready to ditch the car, his friend, also eighteen, pulled out a .357 Magnum revolver — allegedly to intimidate the driver so he wouldn’t chase after them.

In an instant, Johnson saw a flash next to his face: The friend had fired a bullet, killing the driver. Hours later, Johnson was arrested, and eventually he agreed to a plea deal of second-degree murder, even though, according to official court records, he was not the one who had fired the weapon. A judge sentenced him to fifteen years to life in prison and he became eligible for parole — meaning a release back into society — on May 28, 1995 when he was thirty years old.

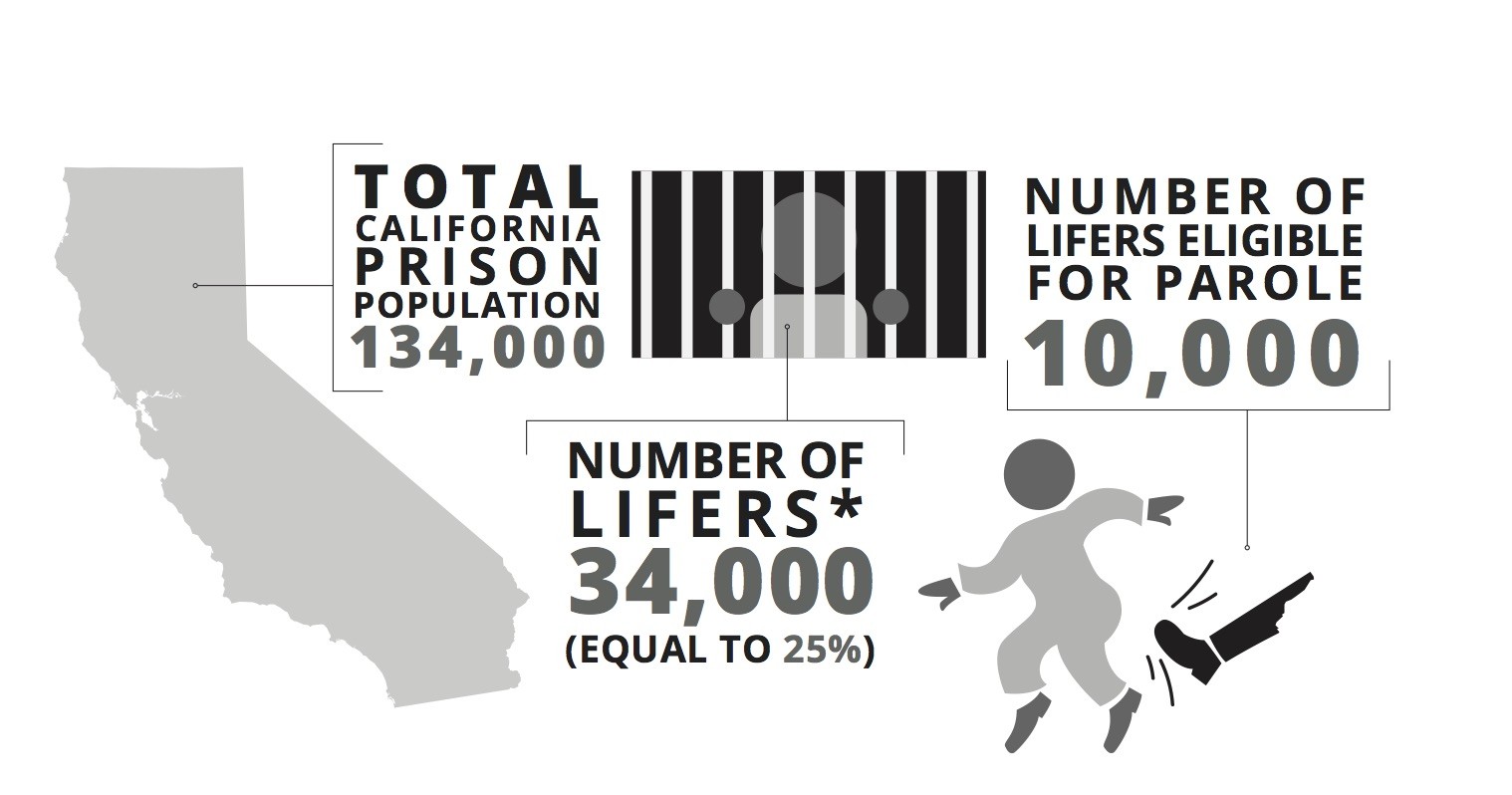

Twenty years after that eligibility date passed, and many unsuccessful parole hearings later, Johnson is still locked up — with little hope of finding freedom anytime soon. He is one of roughly 34,000 prisoners in California currently serving life sentences with the possibility of parole. Known as “lifers,” these inmates represent about 25 percent of the entire prison population in the state. Many lifers are men serving time for first- or second-degree murder convictions. Some have committed heinous acts of violence. Others were caught up in gang- and drug-related crimes that resulted in a homicide that they did not directly commit. And others were convicted under the state’s three-strikes law, which, for some offenders, mandates life sentences after three felony convictions. Lifers typically face sentences of a minimum of 7, 15, or 25 years, and many who serve those full sentences end up incarcerated for much longer. According to UnCommon Law, an Oakland-based nonprofit that supports California lifers and is representing Johnson, there are currently about 10,000 lifers in the state who have served their minimum sentences and are eligible for parole. But they remain confined to prison, trapped in a system that critics say is unnecessarily cruel.

Under state law, a parole board, made up of commissioners appointed by the governor, decides whether an individual is “suitable” for release. The law requires the parole board to release eligible inmates when they are no longer a danger to society. Commissioners are also supposed to remain unbiased and must not deny parole to an inmate merely because of the severity of the original crime.

But interviews with currently incarcerated lifers, recently released lifers, family members of inmates, and criminal defense attorneys — along with an extensive review of parole data and hearing transcripts and in-person observations of parole proceedings behind bars — paint a picture of a process plagued by harsh and arbitrary decisions that force people to stay locked up for many years after they have been rehabilitated. And inmates are regularly denied freedom due to petty disciplinary marks and questionable and biased conclusions of board commissioners.

For the majority of lifers who can’t afford counsel, their fate rests in the hands of state-appointed attorneys, who receive low pay and are usually burdened with heavy caseloads. These lawyers often do very minimal prep work before a hearing, making it easy for veteran prosecutors and tough board members to exploit the obscure vulnerabilities of a prisoner seeking parole. The most marginalized inmates — including those with mental illnesses and people who have previously suffered abuse and trauma — face particularly challenging parole battles (a topic covered in Part Two of the two-part “Trapped” series, which will be published in the January 14 Express).

From a policy and economic standpoint, experts have increasingly scrutinized this sector of the state prison system with the recognition that the continued imprisonment of lifers plays a major role in overcrowding and is incredibly costly to taxpayers. And from a personal and emotional standpoint, the cruel legal twists of the parole process can excessively punish reformed men and women while also inflicting immense pain on the lives of loved ones on the outside. People who committed crimes decades ago, when they were kids, are regularly denied second chances even when it seems they’ve done everything right in prison.

Just ask Johnson. In July 2015, he was denied parole for the ninth time — in part due to an alleged rule violation that was so surprising and arbitrary, he could barely process it when his parole commissioners raised it during his hearing. He had, they said, put his arm around his fiancée while she was visiting him on Valentine’s Day — an infraction that showed he is clearly unable to follow rules and is still a danger to society.

For decades, it was nearly impossible for California lifers to get released. In the 1980s and ’90s, “life with the possibility of parole was the functional equivalent of a sentence to life without parole,” said Kathryne Young, a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University who has closely studied the parole process in California.

According to 2013 statistics (the most recent data available) from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), roughly 70 percent of prisoners are serving out “determinate sentences,” meaning cases in which the courts sentence people to a finite amount of time, after which they are released. About 4 percent of prisoners (those convicted of the most serious crimes) are sentenced to life without the possibility of parole or are on Death Row.

The rest are like Johnson — lifers with “indeterminate sentences” who eventually become eligible for parole and are entitled to hearings to determine their suitability for release. From 1980 to 2008, fewer than 10 percent of the cases before the Board of Parole Hearings resulted in grants of release, according to a 2011 analysis by the Stanford Criminal Justice Center. And for the small group that the board deemed suitable to go home, very few were actually released. That’s because in 1988, California voters passed Proposition 89, which gave the governor the authority to overturn the board’s parole decisions in murder cases.

From 1999 to 2003, Governor Gray Davis reversed virtually all of the parole board’s grants of release. And from 2003 to 2011, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger reversed 60 percent of grants and sent 20 percent back to the parole board for additional review. As a result of the low rate of parole grants by the board and the high rate of rejections by governors, the size of the lifer population as a percentage of the overall prison population has increased dramatically — from 8 percent in 1990 to 25 percent today, according to UnCommon Law. California has the highest rate of lifers of any state in the country, the Stanford report found.

Among the small group of lifers who have successfully reentered society in recent decades, many were incarcerated long after they had served their minimum sentences and had become eligible for release. For example, from 1999 to 2010, 701 lifers who were convicted of second-degree murder — an offense that typically carries a sentence of fifteen years to life — were granted parole and released after spending an average of twenty years behind bars, Stanford found. And for those convicted of crimes that typically bring sentences of “seven years to life,” 227 lifers were released during that same time period. They spent, on average, significantly more than seven years in prison — fourteen years for attempted murder and seventeen years for kidnapping for robbery or rape.

Unlike the rest of the prison population, lifers are statistically unlikely to reoffend — another reason why advocates say California has a moral and financial obligation to send more of these inmates home. Overall, according to the state’s 2014 recidivism report, roughly 54 percent of California prisoners return to prison within three years of their release. The recidivism rate for certain classes of lifers, however, is close to zero. From 1995 to 2011, of the 860 lifers who had been convicted of murder and were later released, only five people returned to jail or prison for new felonies — and none for crimes that carry life sentences, according to the Stanford report. Of 278 lifers released during the 2009–10 fiscal year, only 26 people — 9 percent — returned to prison, according to CDCR. And 25 of them returned because of parole violations. Meanwhile, 54 percent of inmates released during that fiscal year after serving determinate sentences returned to prison within three years.

Advocates of long prison sentences argue that the lifer recidivism rate is extremely low because California’s parole process is so rigorous. But critics say the data clearly shows that many lifers who present an incredibly low risk of reoffending remain locked up for unjustifiable reasons. Studies have further shown that people age out of crime and that people over age forty, and especially those older than fifty, pose a very low risk of committing new crimes on the outside. The state’s own risk assessment tool has concluded that 90 percent of lifers have a low or moderate risk of reoffending — compared to 56 percent of the general prison population, according to the Stanford report.

Reform advocates also have increasingly highlighted how much money the state could save if it regularly granted parole to inmates who have rehabilitated. California currently spends an average of nearly $64,000 per state prisoner each year, meaning incarcerating this population costs taxpayers more than $2 billion annually. If even just 10 percent of the lifers currently eligible for parole were released, the state would save nearly $64 million annually.

Continued overcrowding makes the need for increased lifer parole grants all the more urgent, advocates argue. California prisons are currently at 136 percent capacity, which equates to nearly 30,000 more inmates than the total capacity of its institutions and, prison activists say, can lead to inhumane conditions and inadequate services for inmates.

Still, eligible prisoners with extensive evidence of their successful rehabilitation, personal transformation, and suitability for reentry are routinely denied a second chance at the parole board. For many, that harsh reality is rooted in the fact that they are forced to enter their high-stakes parole hearings without a strong advocate by their side.

On the morning of August 6, 2015, Larry Johnson, an inmate at the California Institution for Men in Chino, an hour east of Los Angeles, woke up feeling prepared and eager for his parole hearing. The board had denied him parole in his first hearing in 2014, and he felt he had accomplished a lot since then and could make a strong case to the commissioners that he was ready to come home. But he was nervous about his attorney, John Ibrahim.

For starters, he hadn’t yet met Ibrahim, the lawyer appointed by the parole board to represent him. Earlier in the year, Ibrahim had called the prison and, according to Johnson, did very short back-to-back phone calls with a number of lifers whom Ibrahim would be representing at upcoming hearings. (Larry is not related to Demian Johnson, the Mule Creek inmate). This was Ibrahim’s official “client interview,” which lifer advocates said should always happen face-to-face. “The phone call lasted five minutes,” the 44-year-old Johnson said in a recent phone interview from prison. “He told me … this is the ‘getting to know me’ process.” Johnson said they went over the very basics of his case file — what self-help classes he had successfully completed and whether he had any serious rule violations during his incarceration (he did not). It felt like the conversation was over before it began. “I was kind of shocked, actually,” Johnson said.

When Johnson finally met Ibrahim in person, the attorney did not inspire confidence. According to Johnson, Ibrahim showed up at the last minute, said little to him, chatted briefly with the commissioners, and worked on his closing statement on his laptop minutes before the proceeding began. Ibrahim was still writing it when the commissioners officially started the hearing, Johnson said. “It was awful from start to finish. There was no connection between myself and the attorney,” said Johnson, who is serving a fifteen-years-to-life sentence for second-degree murder and recently became eligible for parole.

According to Johnson, Ibrahim said little on his behalf during the hearing, and it seemed doomed from the start. The commissioners denied him parole again. Due to a technical error, the board apparently did not properly record the audio, which means the state later had to dismiss the decision and grant him a new hearing, scheduled for April, CDCR records show. (There was thus no transcript of the hearing for me to review.) UnCommon Law is now representing Johnson.

Reached by phone, Ibrahim said he could not recall the specific case, but said it was likely he conducted a phone interview. “It’s just a common practice,” he said, noting that the state doesn’t pay for mileage driving to and from prisons. But he said all his interviews are at least twenty minutes and much more in-depth than how Johnson described it to me. “I can have the same quality of interview over the phone.”

Regardless, Johnson’s frustration with his attorney is common among lifers. Inmates who can’t afford private counsel are entitled to state-appointed lawyers, who are approved by the Board of Parole Hearings and are essentially independent contractors for the prisons. The attorneys get paid a maximum of $400 per client, and that amount is supposed to cover the costs of meeting with the client, reviewing hundreds of pages of case files, preparing for the hearing, travel time to and from prisons, and sitting through the hearing itself, which is often three or four hours long. With such low pay, even the most dedicated attorneys are limited in the time and effort they can devote to clients.

“It is a very underserved population,” said Kate Brosgart, a state-appointed attorney who is based in Berkeley, referring to inmates up for parole. Brosgart, who does lifer parole hearings full-time, said that with $400 per client, she is able to meet with each client once for about an hour usually two months or so before the hearing date and spends about four hours on her own prepping for the date. If hearings go long — sometimes five or even as long as eight hours, depending on the circumstances — she doesn’t receive extra compensation.

In a busy month, Brosgart can have more than 25 hearings — an incredibly intensive caseload that further limits her ability to meaningfully serve her clients. Even with the poor pay and busy schedule, Brosgart said she strives to vigorously defend each client and at least help them get one step closer to release. After I observed her during one of her hearings in November and had an extensive follow-up interview with her about lifers, it was clear to me that she is passionate about her responsibilities and has persisted in the job because she knows how desperately these inmates — whose families often can’t afford attorneys — need competent lawyers. “There’s a real beauty to working with people who have really rehabilitated themselves,” she said. “There are so many lifers who have just spent many, many years at this point becoming educated, becoming certified in different trade areas, who have very important responsibilities in the institution. … There’s nothing that makes that person still dangerous.”

Many lifers with state-appointed attorneys aren’t so lucky to get matched with a caring advocate like Brosgart. She and other attorneys shared with me horror stories that they said are all too common. Brosgart said she has heard of cases in which attorneys essentially give up on their clients — deciding early on that the case is hopeless. They may decline to make a closing statement on their client’s behalf or fail to counter questionable claims by district attorneys, who also participate in hearings and often argue against a parole grant.

Jeremy Valverde, another Berkeley-based state-appointed attorney who represents lifers, said he is forced to depend on his private work and his wife’s salary to subsidize his parole practice. “I really believe in the right for everyone to have fair and adequate representation at their hearing,” he said, noting that when he meets lifers, many of whom have already been denied parole before, they are typically shocked by his enthusiasm and efforts. “They’re used to a certain amount of lethargy,” he said. “[The attorney] may just sit there and say nothing the whole hearing. That’s been the expectation.”

Valverde recently met a lifer with a very troubling story about his appointed lawyer. According to the inmate, the state-appointed attorney had pressured him to “stipulate” that he is unsuitable for parole, which means at the start of the hearing, he would tell the board he is not ready to go home — thus delaying any parole consideration for years. While a delay can be a smart move for someone who is truly unprepared — because the commissioners can deny parole for up to fifteen years — the inmate felt he was ready to make his case, Valverde said. It appeared that the lawyer simply hadn’t done the necessary prep work before the hearing. “You’re essentially trying to deprive this client of his rights to his trial, because you’re not prepared to go forward,” he said.

As some state-appointed attorneys struggle to make a difference within the confines of a process that seems to fundamentally devalue their roles, a small group of private attorneys and advocates are pushing for systemic changes — reforms that would help incarcerated people access the second chances to which they are legally and ethically entitled.

Lifers convicted of gruesome and unimaginable crimes must eventually be released — unless they continue to pose a clear threat to public safety. That is, at least, the directive written into California penal code, which states that the board “shall normally grant parole” the first time any lifer appears for a hearing. What that means is the state essentially has an obligation to release a lifer who is eligible for parole, as long as he or she is not a danger. And the board cannot determine that a lifer is a current risk simply because the original offense was horrible.

Keith Wattley, founder and director of UnCommon Law, the Oakland nonprofit that represents lifers, skillfully reminds commissioners of these kinds of obligations when he appears before the board. It’s hard to imagine someone who knows the ins and outs of lifers’ rights in California better than Wattley. He has been representing lifers in parole hearings since 2000 and has pushed for a wide range of policy changes through advocacy efforts and ongoing litigation. Wattley urges commissioners to grant parole to his clients based on hard facts and the particulars of relevant statutes — instead of letting the officials’ subjective assumptions and personal biases influence these life-altering decisions.

Wattley’s clients run the gamut in terms of offenses and progress behind bars, but he tends to work with people who are ready to do the hard work necessary to turn their lives around and confront the demons of their past that led them to prison. He doesn’t shy away from those convicted of heinous or unbelievable crimes — the ones who often most need his services. These are people who murdered loved ones, had particularly vulnerable victims, engaged in disturbing cover-ups, or committed frightening acts of violence. Most of the twelve commissioners in California who oversee parole hearings — an inmate goes before one commissioner and one deputy commissioner — have extensive law enforcement backgrounds and are reluctant to release these prisoners, Wattley explained. “They’ve spent their lives locking these people up and finding them to be dangerous,” he said. “It takes a lot to retrain them to look at people differently.”

Wattley represents roughly half of his clients pro bono or for reduced fees based on income and often spends months or years getting to know the inmates. He schedules regular in-person visits — having in-depth conversations about a prisoner’s upbringing, the circumstances surrounding the crime, and what he or she has done to change and grow behind bars and prepare for a successful reentry. Wattley closely reviews case files and transcripts of previous failed parole hearings and helps clients chart a path to a successful hearing — advising them on the kind of programming, educational degrees, and counseling they should work on behind bars, both to improve their lives and to increase their chances of getting released. He works with his clients to help them uncover the root causes of why they committed the crime and often guides them to a place of deep and genuine remorse. In practice, he is more of a social worker, case manager, and therapist than he is an attorney and legal advisor for his clients.

Bernard Toller, a lifer whom I met at his parole hearing in November, told me that his sessions with Wattley helped him come to terms with some dark truths about his past and his offense. “To let all that out is actually a relief,” he said in an interview inside Deuel Vocational Institution, a prison in Tracy, as he waited for the commissioners to finish deliberations. “I told him things I never told anyone. Being honest and open was very difficult, but necessary for my growth. … It allowed me to see myself in the mirror.” Minutes later, Toller learned that the board was finally granting him parole — after he had endured several previous denials. Before guards escorted him away from the hearing room, he told me he felt exuberant. “I still have more life to live!”

Since UnCommon Law was formally incorporated as a nonprofit in 2012, 131 of Wattley’s clients have successfully left prison. None have committed crimes after their release, he said.

In recent years, Wattley has pushed to ensure that the state and individual commissioners follow through with various policy reforms, big and small, designed to make the process fairer for inmates. Most notably, in 2008, the California Supreme Court ruled that the state must base its determination of “current dangerousness” on a variety of facts in the record, not just the details of the offense — a game-changer for longtime inmates doing time for serious crimes.

Due to this reform and a number of other changes, today nearly 20 percent of annual parole hearings result in grants of release. Further, Governor Jerry Brown’s veto rate has overall been significantly lower than that of his predecessors. From 2011 to 2014, Brown has, on average, reversed fewer than 20 percent of grants each year.

But when commissioners are biased against inmates, they find ways to circumvent reforms and issue denials, Wattley said. For example, if they want to deny someone due to the disturbing nature of the crime or because they don’t like an inmate’s attitude or comments, commissioners will find a way to argue there is a “nexus” between the offense and a prisoner’s ongoing behavior or lack of “insight” or “remorse” — even when there’s little evidence to back those claims.

In other words, even when the laws and facts are on the prisoner’s side, commissioners often are not — and the consequences can be costly.

Parole hearings can feel claustrophobic and tend to be emotionally and mentally exhausting for everyone in the room. The first hearing I observed started at 8:44 a.m. on a Tuesday in November inside California Health Care Facility, a relatively new prison in Stockton. Up for parole was 47-year-old Antoine Jenkins, who was convicted in 1991 in a murder, robbery, and burglary case tied to a major drug operation that he apparently helped run when he was in his twenties. As is sometimes common in these cases, he did not pull the trigger in the murder, though he was clearly caught up in significant criminal activity for years and was involved in a major drug sale that turned deadly. He was sentenced to 29 years to life and was first eligible for release in 2010 (inmates generally become eligible for parole before finishing the full term of their sentence, usually because of good behavior).

The room that morning was freezing and looked like a small classroom. Jenkins, in a blue prison uniform, sat next to Wattley, his attorney, on one side of a table directly across from Commissioner Michele Minor and Deputy Commissioner Stewart Gardner, who each had desktop computers in front of them. A deputy district attorney from Los Angeles conferenced in by video. Two correctional officers stood guard throughout the hearing. And Express photographer Bert Johnson and I sat in a corner of the room, ten feet or so away from Jenkins.

This hearing, technically Jenkins’ second, was particularly high-pressure for him given the debacle of his first encounter with the board. In 2008, two years before he was eligible for release, Jenkins’ state-appointed attorney told him that he should delay his first parole hearing by one year because ongoing litigation would yield a change in the law that would benefit lifers. But, as he and Wattley explained during the recent hearing, Jenkins unknowingly signed a seven-year “stipulation” — an unnecessarily long delay for someone who was ready to be considered for parole. That meant that 2015, more than two decades after his arrest, was his first legitimate shot at freedom.

At parole hearings, commissioners conduct lengthy interrogations about the inmates’ childhoods and circumstances prior to the crime, the crime itself, accomplishments and discipline behind bars, and post-parole plans. District attorneys then question the inmate, the inmate’s attorney can question him or her as well, and all three of them can make closing statements. The commissioners deliberate on the spot and offer an immediate decision.

Not long after the hearing began, Jenkins broke down in sobs while discussing his late grandparents who had raised him and, as he described it, had given him a good childhood. “I let them down so much,” he said. “It hurts just to think about it.”

He broke down again when recalling a time that he thought his cousin had been shot. Jenkins repeatedly described to the commissioners how his greed and selfishness led him to commit the criminal and violent acts that landed him in prison.

When Commissioner Minor delivered her decision, at 11:45 a.m., three hours after the hearing began and after 36 minutes of deliberations, she offered a lot of praise for Jenkins: He has clearly accepted responsibility for the crime, he presents a reduced risk of recidivism at age 47, he has marketable skills and realistic parole plans, and he has not had a violent rule violation behind bars since 2000. She also noted that, according to the California Supreme Court, the board cannot consider the offense, prior criminality, or unstable social history as indications that he currently presents a risk of danger. But, she argued, various nonviolent rule infractions in recent years show he poses a continued threat to society. He was caught with tobacco in 2008. He was caught with a cellphone in 2012. And in July 2015, he was caught inappropriately grabbing his fiancée in the visiting hall, apparently briefly rubbing up against her. “That was a very selfish thing to do — same thing you were doing at the time of the crime,” Minor scolded, as Jenkins sat stoic, staring forward. “It is disrespectful to your visitor.”

At 11:59 a.m., the hearing was over: Minor and Gardner had refused to grant Jenkins parole and issued a five-year denial. He can petition the board to get an earlier hearing, but if that fails, his next chance at freedom won’t come until 2020.

“When is this nightmare going to end?” Jenkins asked me by phone a few weeks later. “I’m ready — now. You know what I mean? … I know for a fact that I would never come back to prison. … There is no way in hell I would commit another crime.”

His fiancée, Jennifer Chacon, said she was devastated by the denial — especially knowing that her alleged horseplay with Jenkins played a part in it. The idea that he had mistreated her in any way that day was absurd, she said, after I had mentioned to her that officials in the hearing characterized the touching as a sexual violation of her. “It is so ridiculous. If that were the case, why would I stay there? If I felt disrespected, I would’ve left.”

More broadly, she said it’s obvious that Jenkins is a completely different man today than he was decades earlier. “He was 22 when all this happened. … Now, Antoine is almost fifty years old, and you don’t think he’s changed?” she said. “I really want him to be home with me.”

The parole denial echoed the rejection of Demian Johnson, the other UnCommon Law client who failed to get parole in 2015 after he was accused of putting his arm around his fiancée on Valentine’s Day. According to the transcript of the July 2015 hearing, the commissioner in that case, Terri Turner, said of the incident, “It just, to me, demonstrates a pattern of behavior, where you have yet to recognize the boundary lines.”

Turner added: “If you can’t follow the rules and regulations in prison, then it’s difficult to believe that you’d get out of prison and follow the rules of society.” She further criticized Johnson for not taking full responsibility for the incident and seemingly trying to minimize the seriousness of the offense when questioned during the hearing.

But when I recently met Demian Johnson’s mother, Ann Johnson, of Oakland, she provided me with documents showing that her son had every reason to be defensive. Months after his denial, Demian had successfully appealed the Valentine’s Day write-up and had it removed from his file; a sergeant admitted the alleged conduct merited only a verbal warning. The sergeant further wrote: “Mr. Johnson has displayed exemplary behavior and conducted himself respectably and with decency, never disregarding boundaries or the sanctity of the visiting room.”

Hilda Wade, his fiancée, told me she had absolutely no memory of him even putting his arm around her that day.

“It’s like a kick in the gut when you get denied,” Demian told me by phone. “You’re kind of just like, ‘Wow. I can’t win.’ But I realize I can’t think like that. I can’t be depressed. … I feel like I’m fighting the good fight … and in the process I’m also growing and developing. Whatever time I have left, I’m using.”

Jennifer Shaffer, executive officer of the parole board, said she couldn’t discuss specific cases, and CDCR officials also declined to comment on the individual inmates in this story. In a lengthy phone interview, however, Shaffer defended the commissioners, arguing that they make very deliberate, careful decisions that are always based on a wide variety of factors and their obligations under the law. Shaffer, who became executive officer in 2011 and has made increased transparency a priority during her tenure, noted that the state has dramatically expanded training for commissioners in recent years.

“These are very, very difficult decisions made by human beings,” said Shaffer. “These decisions can be very emotional. It’s an extremely meaningful decision. You have somebody’s liberty at stake, and you have victims who have been significantly traumatized, and they’re very afraid. … If you really focus on the law, it gives you a clearer path to a decision. … It’s the only way to really have fair and unbiased hearings.”

Shaffer also said the board has specific guidelines for state-appointed attorneys, which outline the basic expectations for the tasks they should complete when representing lifers at hearings. But, she said, the board is fairly limited in its communication with and oversight of lawyers. “These people are all certified, licensed professionals, and they know what their ethical duties are to their clients,” she said, noting that inmates can file complaints if they believe their representation was inadequate.

But advocates said that better pay and stricter requirements for state-appointed parole attorneys — mandatory in-person meetings, for example — could go along way toward helping inmates defend themselves against denials over petty rule violations. Brosgart, one of the state-appointed attorneys, told me that when she privately represents lifers, she typically charges $4,000 — ten times the state’s rate. “You can have a very different relationship,” she said. “You can work together, give homework assignments, establish excellent parole plans.”

When attorneys have time to closely review case files and discuss with inmates potential flaws in their record, the lawyer and prisoner are both in a much better position to respond to various charges of commissioners and prosecutors, said Wattley.

More broadly, if California had parole commissioners from more diverse backgrounds — with expertise and experience beyond prison and law enforcement careers — inmates would be less likely to face denials for frivolous reasons, Wattley said. And if commissioners were to receive better training about the fact that many types of minor rule infractions have minimal connections to current dangerousness, then the board likely would send more inmates home.

Wattley and Brosgart also said that if lifers received long-term case management from dedicated, in-house social workers, prisoners would be much more prepared to face the board — and better equipped to ultimately return to society. Instead of relying on lawyers like Wattley to help them coordinate their programming behind bars and their post-parole reentry plans, inmates could move toward true rehabilitation in a more holistic way. Upfront investments in prisoners’ recovery could translate to major savings when they get earlier parole dates. And inmates could have more years to reconnect with loved ones on the other side.

Ann Johnson, Demian’s 72-year-old mother, told me that the arbitrariness and cruelty of the parole process has deeply affected her. “It’s taken a toll on me physically and emotionally. It’s heartbreaking. You try not to cry everyday.”

Driving to prison regularly is exhausting for her, and she spends hundreds of dollars a month talking to him on the phone. “It doesn’t get any easier,” she said.

The July parole denial took his family by shock. “I expected him to get a date,” Ann said. “It seems extremely unfair. … He’s a danger to society because he doesn’t follow the rules? I can’t make sense of it.”

Lifers’ loved ones told me that they try not to let the inmates know much pain the denials cause. “It hurt me. I cried so bad,” said Hilda, Demian’s fiancée. “But I didn’t let him know. I didn’t want to burden him. But it hurt me to the heart.”

Antoine Jenkins and Jennifer Chacon’s weekly visits mean everything. “He’s there for me emotionally, and we counsel each other on the situations we’re dealing with,” said Chacon, who lives in Sacramento and is a medical office coordinator. She said they’ve supported each other through various struggles they’ve faced in recent years — Jenkins preparing for the parole board and coping with the death of his mother; Chacon dealing with the hardships of taking care of sick relatives while working full-time.

“It’s like a vacation,” Jenkins said of Chacon’s visits. “You’re up here with all this chaos and you go there and have peace of mind.” He said they talk about sports, politics, church, family, and their life goals.

But the allegedly inappropriate waiting-room conduct in July 2015 cost Jenkins more than just a sizable delay in obtaining freedom. The prison also banned Chacon from visiting him again for several months. Chacon and Jenkins told me they’ve been fighting to get her visitation rights re-approved, but have run into difficulties. When they are finally approved, they will likely only be able to talk through a glass wall at first, Jenkins said. (A CDCR spokesperson declined to comment on Jenkins’ visiting privileges.)

Chacon said it was painful for both of them that she wasn’t able to visit him before his November hearing and help him prepare and stay calm. “We could’ve talked about it face-to-face, maybe rehearsed. … Now all we get are these fifteen-minute phone calls. Try fitting your whole day into fifteen minutes.”

She wants to meet with him as soon as possible so they can also start diligently planning how he can get another hearing date — and figuring out what he needs to do to make sure his next board appearance results in a grant.

Jenkins told me he initially feared that the termination of her visitation rights would create such a strain on them that it might ruin their relationship. But, they both said, they are simply trying to stay positive and strong — and they’re looking forward to when they can see each other again.