When the organizers behind Catchlight, a Berkeley-based nonprofit dedicated to documentary photography and visual storytelling, were deciding on the focus for their first gallery exhibit, there was little debate. They agreed that it should track the changes occurring across the Bay Area as a result of the enormous wealth flowing into the region. “It’s all anyone talks about,” co-curator Rian Dundon said matter-of-factly in a recent interview.

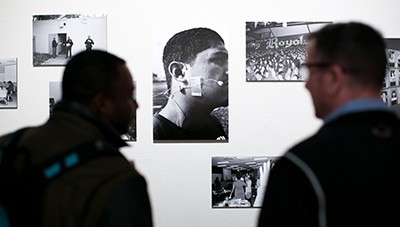

But to say that Status Update, the resulting group show composed of local photographers and documentarians that debuted recently at SOMArts in San Francisco, is strictly about gentrification, would belie the complexity and longevity of the work it features. As Dundon explained, none of the projects are “specifically about gentrification or housing or the economy, but all of the projects touch on those issues in a way that only photography can.”

Although the exhibit was taken down on November 15 following a weekend of talks and other related events, interviews with the participating photographers and other features will gradually be made available online at Catchlight.io beginning in December.

The fourteen participating photographers collectively challenge the viewer to look beyond the dichotomy of villains and victims that has come to pervade gentrification rhetoric by documenting a variety of individuals from all over the Bay Area. Geographically, the projects include San Jose, Stockton, Richmond, Brentwood, Oakland, and San Francisco. Aesthetically, they range from Sam Wolson’s high-contrast, black-and-white frames to the sumptuous, golden hues of Paccarick Orue’s images — from Elizabeth Lo’s documentary made on a bus to Brandon Tauszik’s slow-moving GIFs. But all of the photographers share an unflinching gaze on their respective subjects and an enduring dedication to their projects, which took months or years to capture (one has been nearly a decade in the making). Instead of offering cut-and-dry storylines of winners and losers, haves and have-nots, the photographers offer an entry into the complexity of life in the Bay Area now.

Perhaps the most literal time capsule is Pendarvis Harshaw’s collection of portraits for his ongoing project, OG Told Me. When Harshaw was a teenager, older African-American men would often offer him advice. Years later, he began photographing the men and documenting their stories. While the elders offered varied advice — the pitfalls of drug use and the nature of love and respect among them — Harshaw found that all expounded on the Black male experience.

While Harshaw’s vignettes buoy viewers with their succinct narratives, Wolson’s untitled photo essay concentrating on the life of Oaklander Shannon Fulcher provides a more challenging storyline. If the hallmark of a documentary photographer is his ability to get close to his s

While Harshaw’s vignettes buoy viewers with their succinct narratives, Wolson’s untitled photo essay concentrating on the life of Oaklander Shannon Fulcher provides a more challenging storyline. If the hallmark of a documentary photographer is his ability to get close to his subject, Wolson accomplishes it. The project follows Fulcher as he irons a shirt, hugs his daughter, receives a kiss, screams in anguish, smiles during an embrace, and appears dejected. By probing into both his subject’s most banal and expressive moments, Wolson attempts to offer more than a simplistic story of adversity and redemption.

Similarly, in Orue’s meditation on Richmond’s Iron Triangle neighborhood, There is Nothing Beautiful Around Here, Orue avoids emphasizing the archetypes that the area is best known for: namely, perpetrators of gun violence or its victims, substance abusers, and people living in poverty. In one image, a family celebrates a child’s birthday, but the view is obscured by a large iron fence enclosing the pink tablecloths and bouncy house. It’s as if the photographer is calling attention to the fact that this story — of families in celebration — is typically omitted from an outsider’s view of the city.

“Many of the images in the project function in that way,” Orue explained in an interview. “You get those scenes of celebration, of the will of people to live normal, happy lives, and then you have these subtleties in the images. … It’s that juxtaposition.”

It would be easy to say that Status Update as a whole highlights those juxtapositions — the shimmer of the tech industry’s bubble versus the grit of those left outside it. But, Status Update does not give viewers that satisfaction. As Dundon put it: “We all exist on a spectrum of this change, and we’re not all millionaire techies or impoverished people being kicked out of our neighborhoods … There’re a million ways to experience what’s happening here.”