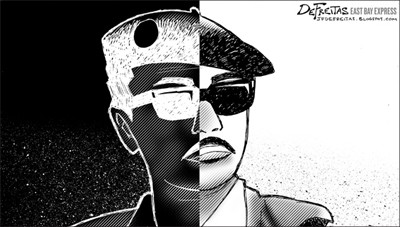

A new report published last Friday confirmed earlier revelations that Richard Aoki, a former longtime political activist and Peralta Community Colleges professor, was an FBI informant for sixteen years. The new report from respected journalist Seth Rosenfeld and published by the Berkeley-based Center for Investigative Reporting uncovered numerous government documents, definitively proving that Aoki repeatedly provided information to the FBI during a time in which he also armed and trained the Black Panthers and was a member of other militant leftist organizations. But while the startling revelations about the iconic Aoki are disturbing, there are also many unanswered questions about his relationship to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

For starters, while the FBI documents that Rosenfeld obtained describe the information Aoki provided as “unique” and of “extreme value,” the records reveal little about what Aoki actually told FBI agents from 1961 to 1977. As a result, it’s not yet clear whether Aoki provided crucial intelligence on the Black Panthers and other organizations — or whether his FBI handlers merely thought he had. The only thing that’s clear from the documents so far is that Aoki routinely talked to FBI agents and gave them written information.

We also don’t know yet whether Aoki had gathered intelligence from the FBI and then used it to help the Black Panthers and other groups he was involved with. That may sound farfetched to some, but the history of spying is littered with cases involving double agents, who convinced their handlers that the information they were giving was “unique” and of “extreme value,” but was actually neither.

Moreover, as a member of militant activist groups who also talked to the FBI, Aoki was in a unique position to know exactly what each side knew about the other. Indeed, in public interviews, Rosenfeld has acknowledged that Aoki may have been working both sides, so to speak. And so, even though Rosenfeld’s reporting has been exemplary, the full story of Aoki and his involvement with the FBI remains untold.

We know for sure, for example, that Aoki, a former US army sergeant, provided arms and training to the Black Panthers. We also know that the Panthers and other groups viewed Aoki as an important, trusted activist; the Panthers dubbed him the “minister of education” of their Berkeley chapter. As such, it seems possible that Aoki may have helped steer the Panthers in ways that allowed the organization to avoid FBI detection.

The only way we’ll know for sure if Aoki really did sell out his fellow activists is if the FBI releases documents that prove the information he provided truly was crucial. Moreover, we probably won’t know whether Aoki also provided FBI secrets to the Panthers and other groups he worked with — until evidence come out that shows Aoki predominantly steered those groups in ways that helped the FBI. In short, the question of whether Aoki was a traitor to the activist cause or a shrewd manipulator of government agents has yet to be answered.

Finally, it should be noted that some of the attacks against Rosenfeld by leftists and Aoki supporters have been out of bounds. Rosenfeld has long been one of the best investigative reporters in California.

Citizen’s Group Misguided

A group of Oakland citizens is planning to try to intervene in the federal consent decree overseeing the Oakland Police Department. The San Francisco Chronicle reported late last month that the group, which includes members of Make Oakland Better Now, a good-government organization, contends that the federal court monitoring of OPD has deemphasized crime fighting in a city with severe crime problems. The group also is worried that things will worsen if OPD ends up in federal receivership. But while the citizen’s group has every right to publicly criticize the consent-decree process and the court monitoring, its planned attempt to intervene in the federal case is misguided.

The reason is that the citizen’s group already has a voice in the consent-decree process (as does every other Oakland resident) through the city’s elected leaders. So by trying to intervene in the federal court case, the citizen’s group is not only directing its concerns to the wrong entity, it’s attempting to place its own ideas about the consent decree above the rest of the city’s residents.

To understand why requires a bit of background. The federal consent decree and the court monitoring of OPD stemmed from the infamous Riders case in which a group of rogue cops abused numerous West Oakland residents in the late 1990s and the early part of the last decade. The reforms in the consent decree, also known as the Negotiated Settlement Agreement, grew out of a lawsuit filed on behalf of The Riders’ victims against the City of Oakland.

Oakland’s then mayor, Jerry Brown, the entire city council, then-City Attorney John Russo, and the Oakland Police Department all agreed to settle the lawsuit and implement the reforms outlined in the consent decree. They also agreed to the independent monitoring process established by the court to ensure that OPD actually enacts the reforms.

In addition to OPD and the court monitoring team, the consent-decree process includes the city itself, which is a party to the settlement and monitors the court process through its City Attorney’s Office; attorneys John Burris and Jim Chanin, who represent The Riders’ victims; and federal Judge Thelton Henderson, who oversees the entire thing.

So, by trying to intervene in the consent decree, the unelected citizen’s group is attempting to do something that Oakland’s own elected leaders have not yet agreed to do: add another party to the federal court oversight process. That’s unfair to the rest of Oakland’s citizenry, especially those who believe OPD should fully implement the consent-decree reforms — and that those reforms, which are designed to limit police abuses, should remain paramount.

Obviously, the citizen’s group is unhappy with the consent-decree process. But like every other Oakland resident, the group already has a forum for expressing its criticisms — it’s called the city council. And if the council and the city’s other elected leaders, who represent all Oaklanders, agree with the group’s concerns, then the city has the power to request changes to the consent-decree process in court. That’s how democracy is supposed to work.