On a dark early evening in November, Channing Woodsum climbs the stairs of Maria’s 36th Avenue apartment building in East Oakland. He is greeted with the message “VIOLENT GANG OR DONT BANG BITCH” scribbled repeatedly on the stairwell walls. On the third floor at the end of a narrow, unkempt hallway, Woodsum knocks loudly on the door. A TV blares from inside, grows soft, and several hushed voices speak in Spanish before a teenage boy tentatively cracks the door.

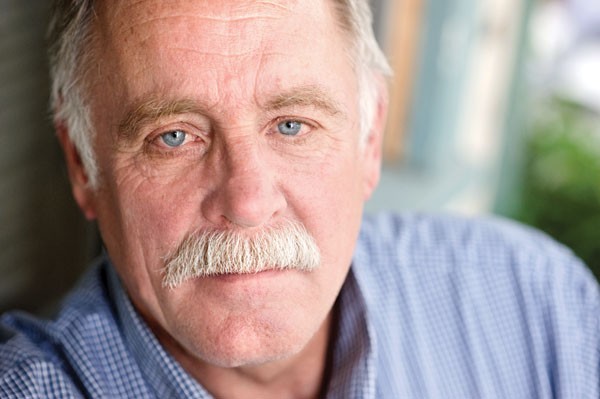

“We’re from Maria’s school,” Woodsum announces in a firm but affable greeting. A tall, brawny 66-year-old, with a guttural voice and glasses that rest on his nose above a bushy grey mustache, he is dressed in his standard garb of saggy jeans and button-down work shirt. Woodsum hands the boy a roughly designed business card. His presence is both jovial and unyielding, a difficult man to slam the door on. “You must be her brother. Are your parents home?”

Woodsum estimates that he has visited more than 1,000 homes in his career. Credits: Chris Duffey

As a teacher, Channing Woodsum often visited the homes of his students. Now it has turned into a full-time job. Credits: Chris Duffey

Channing Woodsum visits the home of a student from Media Academy High. Credits: Chris Duffey

Woodsum almost always shows up unannounced. Credits: Chris Duffey

Woodsum is a veteran of almost forty years teaching English in the Oakland public schools. He retired from the classroom in 2007, but was hired last year by the principal of Media Academy High, a small school in Fruitvale where he most recently taught, to continue visiting students’ homes as the school’s official “Home Visit Coordinator.” While he occasionally attends the homes of high-performing students, the visits are generally intended for ninth and tenth graders who are failing classes, acting out, rarely attending school, or, most commonly, all three. Labeled “the last line of defense” by one school staffer, the visits are sometimes requested by teachers. More commonly, however, Woodsum compiles his caseload by combing through attendance records and report cards. Shortage of supply is never a concern.

In the course of his career, he has become well-known by teachers and students for his visits, of which he’s conducted more than one thousand. Maria’s house is his third visit of the night, and one of the hundred he intends to do throughout this school year.

Primarily intended to encourage parental involvement — typically sparse at Media Academy — the visits offer Woodsum a glimpse into students’ living conditions, particularly notable in a school where many children come from communities plagued by violence and poverty. In a school district that consistently struggles, and commonly fails, to meet state and federal testing goals, many frontline educators argue that poverty and community disenfranchisement are commonly overlooked as factors that strongly influence academic performance.

Woodsum jots down observations and hopes that teachers review them, although he admits to being unclear on how many actually do and how they might use the information to help shape their teaching practices. He describes visits he’s made to students who never complete their homework, only to find homes completely devoid of furniture.

His visits have taken him to some of Oakland’s roughest neighborhoods, where poverty and violence are everyday realities, and certain living conditions resemble those of undeveloped countries. He’s entered homes with suspected child abuse, seen both parents drunk or cracked-out during the day, and found students not living with their legal guardians. In one instance, he found a student who had been left alone for nearly a week, and on a number of occasions, he has had to contact Child Protective Services. It’s not uncommon, he says, to visit students staying in illegal rentals or condemned houses, including whole families living in converted one-car garages. On one visit, he talked with a grandmother who sat in the middle of a living room strewn with garbage, and last year, he visited a home with broken windows and a front door that dangled from one hinge. Among the most depraved conditions he’s seen was a condemned building where one of his students lived in an apartment with a clogged sink and raw sewage in the yard.

“The visit provides a level of insight,” he said. “It gives you a feel of what’s happening; a realistic sense if a kid has support to do homework.”

Woodsum emphasizes, however, that he just as often finds students living in pleasant accommodations with warm households and genuinely concerned, if uninformed, parents. Although caught off guard, most families are generally pleased that the school is actually taking an interest in their kids’ education, and only very rarely has a family member reacted negatively and not let him in. On occasion, he’s even invited to stay for dinner.

Woodsum and a reporter stand awkwardly inside the small one-room apartment. Maria — not her real name — is a slight girl, with deep, sharp eyes, a ninth grader who has already cultivated a .9 GPA and a long list of gripes from her teachers in her first three months of high school. She sits on the edge of a large bed, leaning against the wall, silent and seemingly unconcerned by his visit, a blanket across her lap and hand resting on an open notebook. Next to an inflatable plastic guitar-shaped bottle of Corona beer tacked to the wall is a baseball cap that says “Cockfight” on the brim. A portrait of the Virgin Mary hangs nearby.

Maria’s father sits on the other side of the bed, disinterestedly staring across the room at the TV. He glances at us and returns his gaze to the Spanish-language soap opera on the screen. Maria’s older brother, a hefty young man with a sizable black eye and large abrasion across the right side of his face, sits on a chair next to the bed, finishing a plate of food. Marie, her parents, and two brothers all live together in this one room.

The purported positive impact of teacher home visits on student achievement and parental involvement have spurred the practice in a number of schools around the country in recent years, especially those in urban, low-income regions where student achievement and parent participation are often sorely lacking. While many participating schools follow standard protocols, Woodsum’s approach is fairly unique, and somewhat contentious, in that he almost always shows up unannounced. It’s a routine he insists on, but one that some in his field consider a breach of privacy, an unnecessarily voyeuristic act, and one that raises the issue of how much teachers should really know about their students’ lives.

In 2006, California legislators allocated $15 million for a program aimed at improving communication between schools and parents in districts statewide. The Nell Soto Parent/Teacher Involvement Program, which is being discontinued at the end of this school year due to budget cuts, offered one-time grants of up to $35,000 to pay for trainings and teacher time at schools where a majority of teachers and families agreed to participate in home visits. According to state department of education records, sixteen Oakland schools were awarded the grant.

The model was partly inspired by the Parent-Teacher Home Visit Project, a program that started in the Sacramento school district in 1998 and, after initial positive results, is now its own nonprofit and active in 41 of that city’s largely low-income schools. Intended to involve parents as “co-educators,” the program also encourages teachers to volunteer to participate and receive compensation for visiting the homes of a broad cross-section of their students. And although the goals are similar to Woodsum’s, the approach is a significant departure.

“In our model, we never go unannounced,” said Connie Rose, the project’s Executive Director, noting concern for the families’ time and privacy. “We’re really big on making sure it feels mutually respectful. … It wouldn’t make sense for us to drop in on someone; we’re not interested in assessing them, we’re interested in engaging them.”

But to Woodsum, advance notice would make him miss out on a critical piece of the puzzle. “I like to catch them unprepared,” he said as he drove down a street in Fruitvale in his worn 1980s BMW, looking for a building number. “I don’t give them a chance to straighten things up.”

Despite being large, white, and overtly conspicuous in many of the communities he visits, Woodsum has lived and worked in the Fruitvale district for nearly three decades, and personally knows a handful of students’ families. His wife is Mien, a member of a Southeast Asian ethnic group, and he’s been involved in the local Mien community since 1980. Neighbors refer to him as “Janx-Ong,” or grandfather, a moniker he accepts with pride.

A part-time contractor and landlord — an occupation revealed by the paint chips permanently encrusted in his brawny, calloused hands — Woodsum has also owned upward of 175 low-rent properties in and around East Oakland at various times throughout his teaching career, a few of which his students have lived in. He only recently sold off his remaining holdings, and in an effort to connect with the families he meets, he routinely offers home-related help, whether it is fixing minor plumbing problems, or counseling a family on how to avoid foreclosure.

Back in Maria’s apartment, her mother rises somewhat apprehensively to greet Woodsum. She speaks no English and Woodsum no Spanish. He attempts minor small talk with the younger brother, then asks him to translate (for obvious reasons he almost never asks the student he is visiting about to do the translating). The boy nods reluctantly, and Woodsum begins rattling off details of Maria’s poor academic standing. He reads through all five of her teachers’ comments and the grades she’s received on her first report card. Although the boy translates this news selectively, the mother gets the gist and nods solemnly, her head bowed. Several of the teachers write that Maria is a smart girl with the potential to do well but has a bad attitude that gets in the way.

It is midway through the fifteen-minute visit before Woodsum addresses Maria directly for the first time. He asks her why she’s doing so poorly in math. “He doesn’t even teach, so I don’t even care what he has to say,” she replies defiantly, speaking for the first time since his arrival.

In a paternal tone of voice, Woodsum asks: “But isn’t your goal to graduate high school?”

“Yeah, but it’s not as easy as it is to say,” Maria responds. She pauses, staring down at her notebook. “Never mind, you don’t get me.”

By the end of the visit, Maria has let her guard down slightly, as Woodsum breaks from the academic talk and spends a minute trying to engage her in more casual conversation. He tells her he lives in the neighborhood and before we rise to leave, says: “I’m going to come back in the spring. I hope to come back and show your mom improvement.” Maria stares past him for a moment, and then looks down at her binder. “Hopefully,” she says.

Woodsum stepped into his first Oakland classroom in the spring of 1969, filling a mid-year vacancy at East Oakland’s notoriously rough Castlemont High School. That year, between January and March alone, he says, a total of nine teachers had started the position and abruptly resigned. “When I started, my students said, ‘Oh, you’re not going to last more than a week,'” he recalls, grinning. “It was the beginning of my realization that there needs to be a connection with the school and the community, especially the parents.”

Despite strong discouragement from his principal at the time, who expressed serious concerns for his safety, Woodsum soon began visiting some of his “real problem kids.” After these visits, he recalls, student behavior often improved markedly.

While some kids find themselves in hot water with their parents as a result of Woodsum’s reports, he claims that they’re rarely angry at him afterwards. A few days after Woodsum’s visit, Maria said she had anticipated the whole thing and wasn’t too bothered by it. She added that she might now try a bit harder in school. One teacher at Media Academy noted that Woodsum’s visits often do motivate students in the short term, although the effect usually wears off fairly quickly.

“Students I visit, they have a different attitude toward me,” Woodsum said. “Now I know what they know, whatever that is. I know a little more about their situation. It’s nothing I can really put my finger on, but there’s a difference.”

There have been times, however, where the visits have reaped unintended consequences. Several years ago, Woodsum came to the home of a student nearing graduation whose GPA had rapidly declined. He spoke with the boy’s father, who later beat his son so badly that the student ran away from home and was found weeks later with his mom in Florida.

According to the 2000 Census, 26 percent of East Oakland’s population lives below the poverty line. Of Oakland’s 127 homicides in 2007, more than half occurred in this part of the city. Media Academy is one of four small schools that make up the Fremont Federation. The fenced-in campus on High Street and Foothill Boulevard sits at the base of the Oakland Hills, less than a mile down the slope from some of the most opulent houses in the region. It’s a hub of rival gangs posturing for turf. The school’s buildings are routinely sprayed with tags, which the district spends thousands of dollars annually to paint over. Nearly every year, at least one student is shot and killed, often within blocks of campus.

Media Academy’s roughly 400-member student body is incredibly diverse (with the notable absence of white kids, who comprise less than 1 percent). According to district records, the student body is roughly half Latino, with a significant number of first-generation English language learners. About a third of the students are African American. South Asians, Pacific Islanders, and a handful of Middle Eastern students make up the remaining students. The number of students living at or below the poverty line is high, and more than half qualify for free lunch.

Last year’s graduation rate at Media Academy was just over 50 percent and only a fifth of students fulfilled the requirements to attend a four-year California college. Due to consistently falling test scores over the last few years, the school was recently branded with a red stamp. Under the gun, it now has up to four years to significantly improve its scores. Failing to do so could result in the state intervening, firing the principal, and replacing teachers. In the worst case scenario, the school could be shut down.

“The district looks at numbers, but it’s not just the district, it’s the state and the federal government too,” said Media Academy Principal Ben Schmookler, a strong proponent of Woodsum’s visits. “It’s all based on how students do on tests.” It is shortsighted, he believes, to evaluate academic performance without thinking about the environment students live in. “They don’t take other factors into consideration. … The problems we have are a direct extension of the problems (students) are facing.”

While most of the parents Woodsum speaks with seem genuinely concerned, most are also woefully unaware of their child’s performance before he fills them in. Schmookler finds that frustrating. “How did you not know that your student has missed 75 classes?” he asked. So along with hiring Woodsum, he has implemented several other programs to increase parental participation and establish a stronger link between the school and its community, including student exhibition nights and a community week. “If parents aren’t going to come to us, we’ll go to them,” Schmookler said. “It’s a really good opportunity to not only let parents know how their kid is doing, but also let us know how the student is living.”

Several years ago, Schmookler himself paid a visit to an angry female student who had been having consistent outbursts in class and overwhelming her teachers, who were at a loss for how to manage her. Schmookler later informed his staff of the visit, describing the girl’s neighborhood as a war zone. Her house was a disaster, the front door was kicked in, and a sock took the place of her broken-off door knob. Although he was not certain how the teachers would use that information, he says he felt it important for them to be aware of — information that could potentially reshape their perspective.

“Basically, what we’re really trying to do is identify students who need help,” Schmookler explained. “If anything, it’s just a way of understanding.” If a student has really bad behavior, he adds, a home visit might shed light on where it stems from. “It gives you an idea of why they’re so angry … and it helps you realize it’s not their fault.”

The surprise visits also serve to update the school’s often inaccurate student contact information. Many students frequently move, don’t live with their parents, or have had phone lines cancelled — all further hurdles to keeping parents in the loop. It’s not uncommon for Woodsum, who seems to enjoy the thrill of the chase, to assume the role of detective, at times spending a good part of an evening just tracking down the house of a single student. On one attempted visit, he arrived at the listed address only to talk to a man who, a few minutes into the conversation, confessed he’d never heard of the student in question. Woodsum later discovered that the girl had indeed lived there at one time, but had since moved to her aunt’s house outside of Oakland. Not surprisingly, he believes, the perennial lack of permanency and stability common among many students has a direct impact on their performance in school.

Media Academy senior Elizabeth Rodriguez, whose mother received a visit from Woodsum last year due to her poor attendance and a sluggish GPA, said it was the push she needed to get in gear. “When Mr. Woodsum came, it made me realize it’s important to go to school everyday because colleges look at that,” said the seventeen-year-old, who is now the news editor of the school paper. “I knew my teachers asked for him to come because they cared about me.”

Rodriguez wrote an article about the visits for her paper. “I interviewed a girl who was mad and other students didn’t think it was cool,” she says. “Most thought it was bad, but they also knew it would help them.”

Throughout his teaching career, Woodsum has embraced opportunities to connect with his students in a manner more personal than many of his colleagues have felt comfortable with, including taking a number of them on weekend trips to a ranch he owns in Mendocino County. “Some teachers don’t even want to know their students,” he said. “They don’t want to know anything about them. Part of it is fear, like they’re letting their guard down.”

It’s around 8 p.m. and Woodsum is doing his final visits of the evening. He knocks on the door of a compact two-story house in an attractive, new development on 65th Avenue. A woman answers from the second floor. Woodsum calls up to her, asking if it would be okay to take ten minutes of her time. A moment later, the woman appears at the door, looking displeased. “Not really,” she said. “I wasn’t expecting anyone. I’m here by myself and I’m not expecting no man in my house.”

Woodsum explains that he wants to discuss her son, a ninth grader who is failing nearly all of his classes, and she agrees to talk at the door, but doesn’t let him in. He hands her a card, which she tucks into her shirt top.

As Woodsum reads through the less-than-complementary figures and comments, the mother looks increasingly defeated. “I don’t know if this is puberty or something else he’s going through,” she says. “He’s being hard-headed.”

“If he doesn’t shape up, he’s headed for the streets,” Woodsum tells her. The mother nods. “I don’t know what’s going on or where he is,” she responds. “I don’t have a male figure. No uncles. I’m trying to do my best.”

Woodsum says good-bye and the mother genuinely thanks him for coming. He drives down the block and points to a large group of teenagers gathered on the corner. “Her kid is probably there,” he says. “You see situations like that where the parent is clearly at a loss to exert pressure. … They ask me, ‘What am I supposed to do?’ I’ve seen that so many times. I wish I had more tools to offer.”

Matthew Green worked as a journalism teacher at Media Academy High.