Del Close spent his life improvising comic, and sometimes not-so-comic, situations, and teaching eager would-be actors and comedians how to do the same. By most measures he was fantastically successful. Anyone who could claim to have coached Amy Poehler, Bob Odenkirk, John Belushi, Eugene Levy, Stephen Colbert, Tina Fey, Jason Sudeikis, Andrea Martin, Mike Myers, Gilda Radner and John Candy—to name only a few of the players under Close’s direction at one time or another—on how to sharpen up their performing skills, must have been a very rare individual.

Indeed, according to For Madmen Only Director Heather Ross’ rewarding documentary spelunking expedition into the life and career of the erstwhile fire-swallower from Manhattan, Kansas, Del P. Close was as insanely complicated as any legendary theater mentor should be. Of course, some would say he was just plain insane. And yet today, 22 years after his death at age 64, his influence is still seen and heard in the work of everyone from Bill Murray and Catherine O’Hara, to Adam McKay and Ike Barinholtz. Close had a motto: “You have a light within you. Burn it out.”

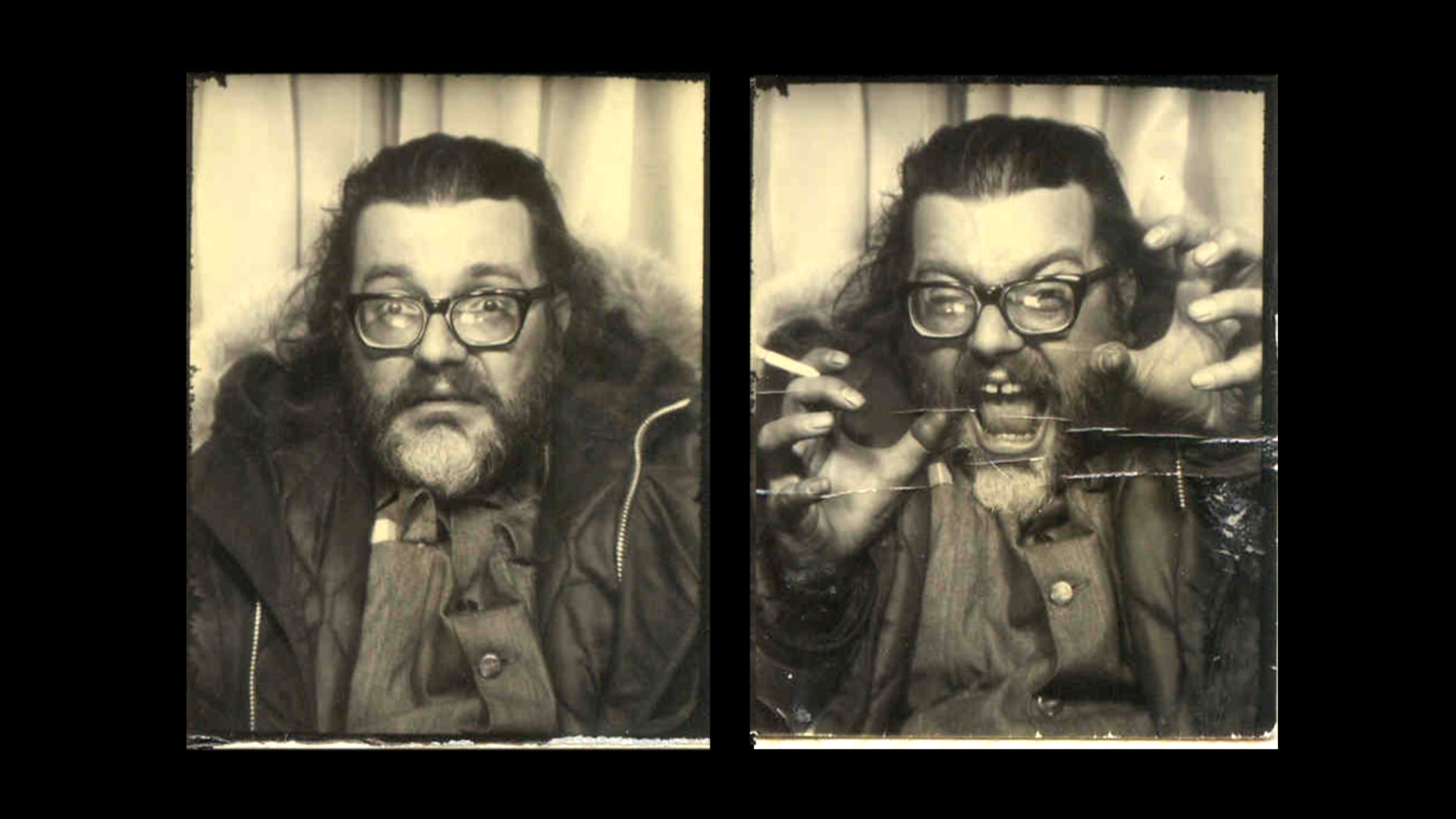

There was a persistent darkness at the edges of Close’s trademark improv scenes. Several of the doc’s talking heads point out the menacing overtones that run through the work—“Should I be scared, or should I be laughing?” Should we believe the probably apocryphal story of the time his father committed suicide in front of him by drinking battery acid? In his early years, Close clearly brought a little danger to his comedy, for audiences bored with Bob Hope. That sense of menace obviously rubbed off on Belushi and Dan Aykroyd, for instance. But, asserts another colleague, “It was hard to follow Del out to those reaches he went to.” More than one of the vintage videos of Close’s workshops ends up with the whole cast lying “dead” on the floor.

To her credit, filmmaker Ross (Who Do You Think You Are?) firmly tackles the artistic/philosophical tiff between Close and Bernie Sahlins—owner and producer of Chicago’s The Second City, temple of American improv—during Close’s fabled tenure there. Sahlins disdained long-form improv in favor of rehearsed material, which was safe and brought in money; people wanted to laugh. The actors, however, loved Close’s raw improv. The rift deepened when paying audiences didn’t particularly buy all that chaos.

Close-directed sketches suffered a nagging failure rate at Second City. His remedy for that was typically quixotic: “What’s the worst thing that could happen? Now, let’s play with it.” Close’s approach, says former Second City Director Joe Keefe, was to relentlessly seek “human behavior in extremis.” But living your professional, and personal, life on the edge took its toll—witness Belushi, Candy, Farley and others. Close himself was actually institutionalized at one point. His 1999 death from emphysema capped years of serious drug abuse.

Tales of Close’s exploits abound. The doc’s graphics are built around DC Comics’ confessional Wasteland series—Close co-wrote it with John Ostrander—featuring the director in helter-skelter close-ups. He dropped acid with the Merry Pranksters in San Francisco. Close’s nutty cameos in Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables, as a sneering Chicago alderman, and in Chuck Russell’s The Blob, as the deranged Rev. Meeker, are justly renowned, as was his showbiz partnership with comic Charna Halpern for ImprovOlympic classes and shows in the 1980s, in which he finally bridged the laugh gap. And then, alas, there’s the story of Yorick’s skull.

But Close never achieved the same level of fame as some of his followers. It was whispered long before his demise that improv had reached a dead end around the nagging question: Which is more important, the cast or the improvisatory method? In the spirit of his “Do-It-Yourself Psychoanalysis Kit” skit, For Madmen Only burns brightly and recedes with a wink and a nod. Crazy how that happens sometimes.