Just like that, a man who’d toiled in obscurity through decades in public life had done the impossible: defeated Hillary Clinton in a state that, until that night, had always had her family’s back.

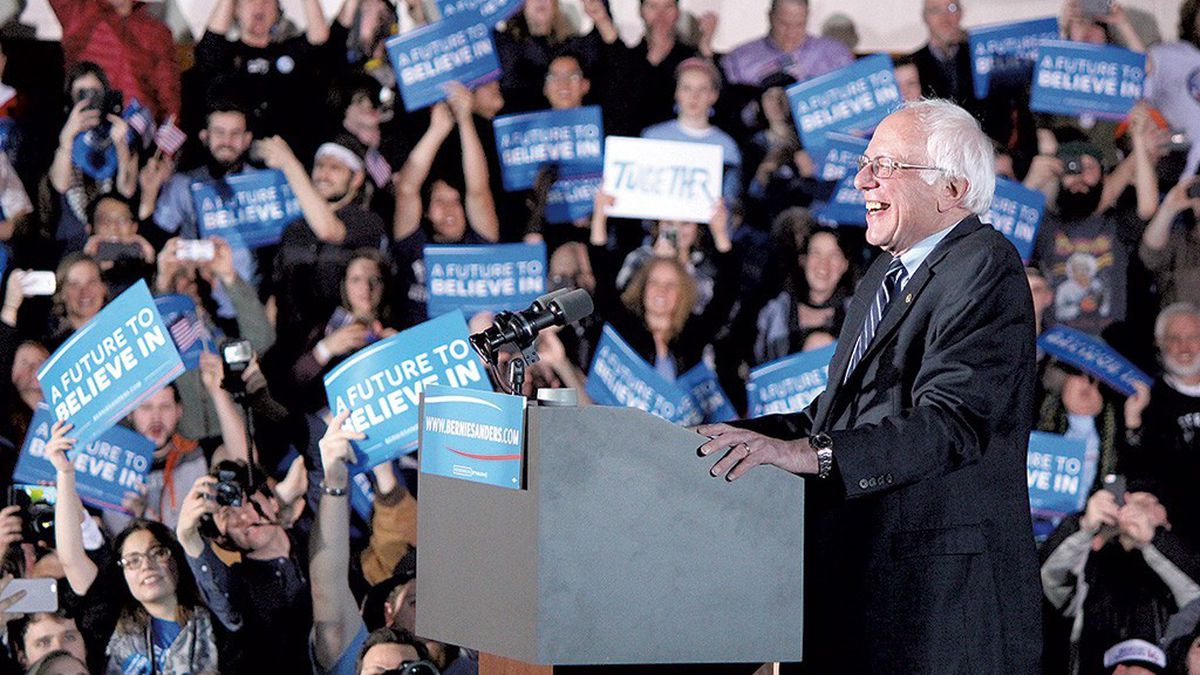

Eighty minutes later, after watching Clinton concede on a television screen suspended from the rafters, the crowd erupted as Sanders appeared onstage.

“Together,” he said, “we have sent the message that will echo from Wall Street to Washington, from Maine to California — and that is that the government of our great country belongs to all of the people and not just a handful of wealthy campaign contributors and their super PACs.”

With the nation watching, some for the first time, Sanders delivered a nearly half-hour speech that has grown familiar to Vermonters over the years — a speech that even Clinton had begun to mimic in her remarks earlier that evening.

“Tonight, we served notice to the political and economic establishment of this country that the American people will not continue to accept a corrupt campaign finance system that is undermining American democracy and will not accept a rigged economy,” he said.

Sanders credited his victory to, as he put it in his native Brooklyn-ese, a “yuuuge voter turnout.” His supporters, imitating the candidate they hope will be president, interrupted him and yelled “yuuuge” right back at him.

The Vermonter’s margin of victory also appeared pretty yuuuge. Sanders swamped Clinton by 21 percentage points.

[jump] Even the Clinton campaign couldn’t spin numbers like that into a positive, though it had spent the week lowering expectations and playing up Sanders’ advantages in a state that neighbors his own.

Sanders’ success was about more than demography or geography. It was about more than his 108 paid staffers in the state, his 18 field offices and his 7,200 volunteers. It was about more, even, than his 3-1 television-advertising advantage in the weeks leading up to the primary.

It was about the message Sanders delivered and the messenger who delivered it.

Sanders landed at Manchester-Boston Regional Airport a week ago Tuesday with the political winds at his back. His “virtual tie” at the Iowa caucuses had electrified his campaign, filled its coffers with another $3 million and rattled Team Clinton.

The two candidates quickly engaged in what would turn into a days-long war of words over who was the real progressive in the race.

“A progressive is someone who makes progress,” Clinton argued Thursday night during an MSNBC debate at the University of New Hampshire. “That’s what I intend to do.”

It was the first time she and Sanders shared a debate stage since former Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley dropped out days earlier — and the difference in tone and tenor was palpable. Clinton lit into her rival for making promises she said he could not keep, while Sanders continued to attack her ties to the financial sector.

Both candidates had their moments, and both left with wounds. Clinton failed to put to rest questions about the more than $1.8 million in speaking fees she has received from Wall Street banks, while Sanders continued to look stumped by the most basic foreign policy questions.

Out on the campaign trail, the senator tested new lines of attack. Speaking at the Rochester Opera House on Thursday, he alluded to his opponent’s shifting policy positions, saying that it was “easier to apologize for a bad vote fifteen or twenty years later, when the tide has changed” than it was to “stand up, even though you are outnumbered, and cast the right vote.”

Friday night at the New Hampshire Democratic Party’s annual McIntyre-Shaheen 100 Club Celebration, Clinton tried to reach out to the young voters who had largely abandoned her for the Sanders campaign. Speaking to thousands of party activists at Manchester’s Verizon Wireless Arena, she recounted her days campaigning for Eugene McCarthy in 1968.

“I learned what you all are proving every day: You can make change without being elected to anything,” she said. “So I respect not only your enthusiasm but also your seriousness about helping to make our country what it can and should be.”

But Clinton’s words seemed to fall on deaf — or, perhaps, absent — ears: Sanders had addressed the crowd an hour earlier and most of his supporters had immediately left the building.

Over the weekend, the two rivals went their separate ways: Sanders to New York City to appear with comedian Larry David on Saturday Night Live and Clinton to meet with the mayor of Flint, Michigan, to discuss the city’s contaminated-water crisis.

But the campaign didn’t stop just because the candidates left the state. Clinton’s top allies made waves when two of them — former secretary of state Madeleine Albright and feminist icon Gloria Steinem — appeared to disparage women who had chosen Sanders over Clinton. Former president Bill Clinton went even further, launching a harsh attack on Sanders Sunday afternoon in Milford — accusing the candidate of hypocrisy and his supporters of sexism.

Sanders responded the way a front-runner might: by ignoring it. During his final day of campaigning Monday, he barely mentioned the former secretary of state. Whisked around the state in an eleven-vehicle Secret Service motorcade, the senator kept his focus on his core message, from Nashua to Durham.

“Tomorrow is a very big day,” he told several hundred students Monday night at a get-out-the-vote concert at UNH. “I hope that at the end of the night, New Hampshire will have told America that we are no longer accepting establishment politics or establishment economics — that we want this country to move forward in a different direction.”

With New Hampshire in the rearview mirror, Sanders now turns to a pair of states — Nevada and then South Carolina — where Clinton appears to have certain advantages in terms of organizational strength, name recognition and cachet with nonwhite voters.

“She got here earlier,” said Jon Ralston, a longtime reporter and political analyst in Nevada. “She hired all the right people from Obama and Clinton ’08. They have the infrastructure set up. They’ve been here almost a year now.”

But Jeff Weaver, Sanders’ campaign manager, says the Vermonter is ready to compete in the Silver State.

“In Nevada, we’ve got over four dozen staffers on the ground,” he says. “We’ve got more field offices than any other campaign.”

Like Iowa, Nevada employs a caucus system to allocate delegates. But unlike Iowa, it has only served as an early-nominating state since 2008.

“So we need to make people who support Bernie know that there is a caucus going on and where it is and what time it is and how you participate and what have you,” Weaver said.

Nevada, which holds its Democratic caucuses a week from Saturday, is the first state in the process with significant populations of Hispanic and African-American voters. That’s led some to conclude that Sanders won’t find traction there, since he tends to draw more support from white liberals. But despite the state’s diverse population, whites accounted for nearly two-thirds of Nevada’s electorate in the 2008 caucuses.

A bigger challenge could be reaching voters who live outside the state’s population center of Las Vegas. In 2008, Clinton won Nevada’s popular vote by turning out Clark County voters in droves, but Obama’s strategic focus on delegate-rich regions netted him one more delegate than his rival.

“The bottom line is that what Hillary has to do is use her institutional advantages, endorsements, her ability to tap into the infrastructure she’s built up,” Ralston said. “And what Sanders has to do is get new voters registered and engaged on the day of the caucuses.”

A week after Nevada comes the South Carolina primary, which awards 53 pledged delegates — more than twice as many as New Hampshire’s 24. Its Democratic primaries boast a majority-black electorate.

The Sanders campaign has invested heavily in South Carolina — it already has more than fifty paid staffers on the ground — and has particularly focused on wooing Black voters. But according to Scott Huffmon, a pollster and political scientist at Winthrop University, Sanders will have a tough time breaking through Clinton’s “strong ties” in the African-American community.

“I expect there to be a lot of movement toward Bernie Sanders, but not enough,” Huffmon said. “It is simply such a different constituency.”

Sanders himself sounds confident. He told reporters during a press call last Friday that his Palmetto State staffers “are feeling very, very good” about his prospects there.

“Let me just say this — and people can play it back a month from now,” he said. “I think we are going to do a lot better in South Carolina than people think we will.”

Joining Sanders on the call was a critical new ally: Ben Jealous, a former president and CEO of the NAACP. Referring to Obama’s come-from-behind victory in the state in 2008, Jealous said, “I know how things can turn very, very quickly.”

That year, an unexpected win in Iowa bolstered Obama in South Carolina. This year, Sanders’ New Hampshire blowout could do the same for him.

Three days after South Carolina comes the biggest test of all: Super Tuesday. That day, eleven states — including Sanders’ own — will cast ballots or hold caucuses.

“It’s obviously a challenge in terms of allocation of resources,” Weaver says. “I mean, you have Vermont, and you have Texas … In terms of television advertising, you could spend your entire presidential budget in Texas.”

One advantage the Sanders campaign has is that, unlike the Republican nominating system, the Democrats have no winner-take-all contests. That means that even if Sanders wins only 40 percent of the vote in a state, he’ll still be racking up delegates.

“That’s the beauty for us: It’s all proportional,” Weaver says. “The key is how you maximize your delegates.”

Also key will be funding a prolonged and dispersed television advertising war. Tad Devine, Sanders’ senior strategist, thinks the campaign’s ability to attract and retain small donors will keep his boss in the game longer.

“That is one of the great strengths of this campaign — not just the amount of money that we’ve raised, but the way we’ve raised money,” he says. “We’re building a big, national campaign.”

They’re not the only ones. And they’re up against a rival who, in 2008, learned a thing or two about waging a protracted fight for delegates.

Clinton also brings to the table certain strengths that Sanders will never be able to match: an auxiliary war chest in the form of three super PACs and a massive advantage among so-called “super delegates” — party leaders who can choose to support whomever they want. According to the Associated Press, Clinton has already locked down 362 of 712 super delegates, while Sanders has won the support of just eight.

“This is a delegate race,” said Clinton campaign manager Robby Mook. “We’re not looking to win every single contest every single time. We have a strategy and a plan for the long term.”

To win the party’s nomination, a candidate must win the support of 2,382 of 4,763 delegates at the convention. So far, excluding super delegates, just 66 have been awarded.

In other words, it’s gonna be a long haul, with a lot of mile markers.

But this week, at least, Sanders is in the driver’s seat.

This report was originally published on SevenDays.com