State lawmakers want to loosen CalWORKs job requirements so people keep cash benefits. Congress’ debt limit deal could curb that

Just as Republicans in Congress are moving to beef up work requirements for people who receive welfare, California lawmakers are moving to do the opposite.

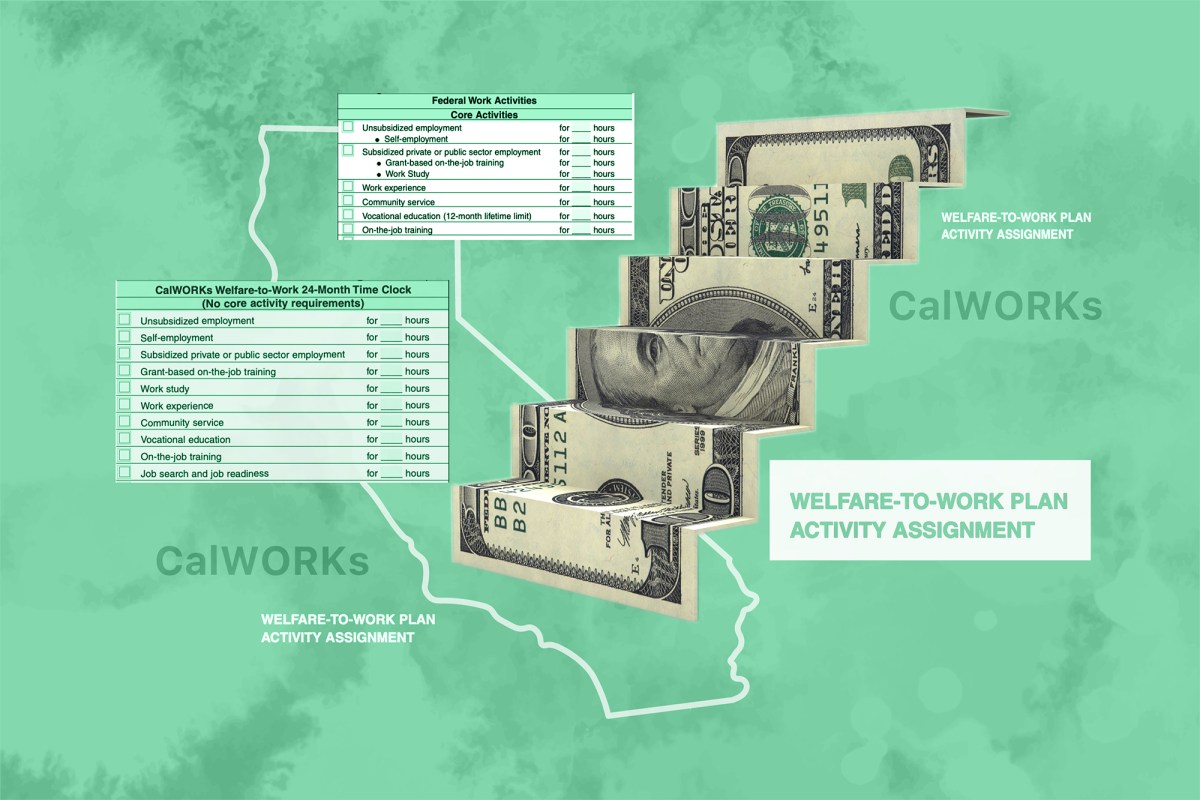

Included in a recent state Assembly budget proposal, and in a bill the Assembly passed last week, is a plan to remake CalWORKs, the state’s federally funded cash welfare program that requires recipients to work or search for jobs using a list of approved activities.

Under the proposed state changes, recipients would gain greater flexibility to participate in activities such as going to school, domestic violence counseling, addiction treatment or mental health care. The proposal, estimated to cost $100 million, also would lessen financial penalties if recipients violate work rules.

That would make it likely that fewer recipients would get jobs and more likely California would miss a key federal work standard, for which it could be fined.

The goals of the proposed changes are to address practical barriers to employment that CalWORKs recipients—some 340,000 of the poorest families in California—experience, and make it easier for more families to qualify for cash assistance.

And, to prod California’s 58 county social service agencies to carry out the plan, the proposal also would shield counties from potential federal fines.

The efforts come at a fraught moment in a decades-old national debate: Should welfare be a flexible source of emergency aid for families in financial crisis, or an engine to push low-wage single parents to join the workforce?

Congressional Republicans, led by House Speaker Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield, have pushed to institute stricter welfare work requirements in a bill to raise the nation’s debt ceiling.

The deal McCarthy struck with President Joe Biden—which the House passed last week and the Senate the night after—includes changes in federal welfare rules that would make it harder for California to make its work rate meet federal targets. Failing to meet that work metric could cost the state $185 million out of the $3.7 billion a year it gets in federal welfare grants.

In previous years, the federal government has threatened California with fines but never forced the state to pay them, advocates say.

Officials at the California Department of Social Services declined repeated requests for an interview about the state’s welfare policies.

For years, advocates have pushed to extricate CalWORKs from the strict federal welfare-to-work rules of the 1990s. Those rules touched off dramatic declines in families receiving public assistance and defined the nation’s cash aid system for a generation.

Proponents of work requirements—Republicans and Democrats alike during the 1990s—said people using social safety net programs should be required, or prodded, to work. They said it would ultimately reduce poverty and dependence on public benefits.

A landmark federal law in 1996 began requiring each state to certify that certain percentages of cash aid recipients were working, or participating in a specific list of job search activities, for the state to continue receiving federal welfare grant dollars.

Federal reports show declines in welfare enrollment after 1996 did not come with corresponding drops in the number of families poor enough to qualify for welfare. Though caseloads also plunged in the Golden State, today families getting cash aid in California make up nearly a third of the nation’s beneficiaries.

Research shows that work requirements led to some increase in employment in the 1990s, but evidence from more recent years is less clear, partly because so many people left the welfare program. A Congressional Budget Office review this year found a “substantial” increase since the 1990s in single mothers who have no income from either work or cash aid.

Advocates have long called work requirements counterproductive and racist, based on stereotypes about “welfare queens” who refuse to work.

California’s cash aid program has been caught between the two ideologies. The state never fully embraced the strict policies of 1996.

While many states slashed welfare rolls—opting instead to use their federal grants on other programs—California continued giving cash assistance. Unlike some other states, California kept cash aid going to children even after their parents’ benefits were cut for violating program work rules.

California also exempts many families from work rules. For those subject to them, the state in 2012 created a more flexible list of activities beyond the strict federal definitions of work.

The state is risking that some recipients won’t count toward the federal work metric. It’s a path other liberal states have taken, said Heather Hahn, a national expert at the Urban Institute.

“States are doing these things that can be seen as workarounds, because working with the (federal rules) feels counter to their goals of helping people achieve economic success,” Hahn said.

Cathy Senderling, director of the California Welfare Directors Association, said giving recipients experiencing those challenges a list of required activities can create “adversarial” relationships with social workers.

Parents can be on CalWORKs for up to five years. Those who leave and find work often bring home low earnings.

Just before the pandemic upended the economy, 18,000 former welfare recipients made income from jobs a year after leaving CalWORKs, according to California’s Department of Social Services. In the first three months of 2020, those former recipients earned an average of $5,800—about $23,000 annually.

Assemblymember Joaquin Arambula, of Fresno, and advocates are pushing a proposal that loosens many of the state rules in favor of a more individualized approach.

Instead of giving recipients a list of allowable welfare-to-work activities to complete, county social workers would come up with a plan that takes into account recipients’ individual circumstances and addresses needs for child care, mental health care or other social services.

“Today counties are asking recipients to meet certain requirements, and we’re saying recipients should be able to come to counties and say, ‘These are the things I need as a family first,'” said Christopher Sanchez, a policy advocate at the Western Center on Law and Poverty.

The state proposal includes paring back sanctions, which are penalties counties impose on recipients who don’t follow their welfare rules. Sanctions come in the form of cutting off cash aid for the adult; advocates say it’s counterproductive to punish struggling families by further restricting benefits.

Arambula’s proposal would essentially eliminate sanctions if recipients can’t complete their plans because of a lack of child care, or “physical, mental, emotional, or other family circumstances.”

Like all major changes in social services, how this policy gets implemented would depend on the county welfare agencies responsible for the rollout.

Sullivan, in Yolo County, said some caseworkers believe the threat of sanctions is “one of the only tools they have to get people to change their lives.”

He predicted the proposal would run into a cultural divide among county caseworkers, who are split on how rigid and rule-based welfare should be.

“You can’t legislate a culture shift,” he said.