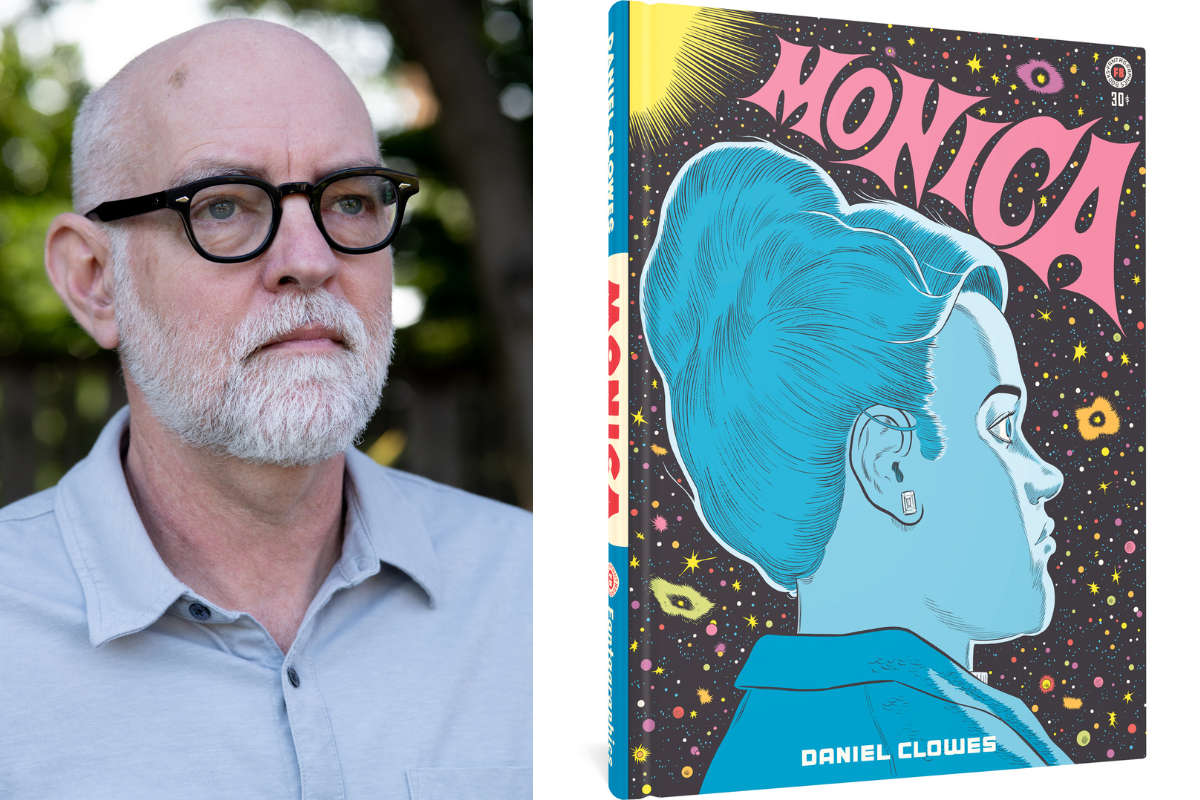

A woman with a beehive hairdo appears on the cover of Daniel Clowes’ graphic novel, Monica. The color of her skin is the same shade of blue as Shadow Lass, a character drawn in the DC comic book series, Legion of Super-Heroes. Clowes draws his protagonist’s face in profile. Monica is looking away from the reader and up into a night sky filled with constellations and distant planets. She isn’t a caped superhero about to fly to the heavens, but the book does contend with the theme of dislocation that regularly recurs in comic book origin stories.

For Monica, her sense of dislocation is both internal and external. Essentially orphaned at a young age—not unlike Batman, Spiderman and Superman—she wanders through the narrative in search of her own identity, a sense of purpose and the feeling of home. As the pages turn, Clowes creates trials and tribulations for the character, increasing the odds against her. The author invents wild tangents to fill in her backstory while Monica directly addresses the reader with episodes from her disturbed and disturbing past.

Clowes doesn’t portray Monica as an unreliable narrator. He grounds each panel in a recognizable state of realism. Steam rises up from a mug of tea. Telephones, televisions and radios appear as familiarizing details inside apartments and houses. Outside, people walk along paved city streets or ramble beneath trees on country lanes. But as Monica’s story gathers momentum, the author starts to depict a parallel universe that is less reliable—a Grimm’s Fairy Tale that incorporates unexpected elements of the uncanny alongside sci-fi and horror tropes.

In the comic book series Watchmen, a morally compromised superman, Doctor Manhattan, is also drawn with the same blue skin as Monica’s on the Monica book cover. In Watchmen, the reader witnesses the pale-skinned Jon Osterman transform into Doctor Manhattan. Monica never undergoes that kind of physical transformation. Throughout Monica, her white skin remains defenseless and her psyche is receptive to harm.

The first significant intimation that Monica exists in a parallel universe takes place when she retreats to her family’s lake cabin after her grandmother’s death. In the process of grieving the woman who raised her, her late grandfather’s voice calls out to her from a radio. She is disbelieving when he first makes contact. But as they begin to converse, he tells her things about their family life that only he would know. Her grandfather also reveals the uglier aspects of his soul. Monica’s sentimental or idealized version of him isn’t sustainable, even if his spectral presence springs from her own imagination. She can’t find comfort in the recesses of her own mind.

The subplots in Monica unloosen the anchors that initially hold the story close to the boundaries of realism. In one, a young man returns to his hometown after a prolonged absence. The placement of his narrative in the novel reminded me of the shipwrecked man’s story in Watchmen. With some degree of subtlety, it functioned as a supplement to and as a commentary on the main plot. Here, the wanderer, too, runs parallel to Monica—but Clowes crafts this secondary story as a pagan Wicker Man-like enigma. He learns that a group of blue-skinned citizens are aliens who control the townsfolk. This information doesn’t help him to escape his fate.

Monica’s fate is also sealed before she’s even brought into the story. Clowes builds our interest in her by depicting the American era she was born into, circa the late 1960s and early 1970s. A time of wars, cults and a cultural revolution. Many of us who grew up then can recognize our parents’ flaws and their flawed reasoning in Monica’s. The author isn’t writing a redemption story, either for Monica or for the society that batters and bruises her.

In 2017, I interviewed Clowes when he was promoting the film adaptation of his graphic novel, Wilson. I asked him about the tone of the movie, which was lighter than his book. At the time he said, “The thing about a comic is, it’s very forgiving of a grim tone. You can be as brutal as possible in a comic and somehow it doesn’t wear down on you.”

As she tries to navigate her life, Monica doesn’t arrive in a place of solace. She doesn’t end up peacefully contemplating the stars. In that respect, the cover of the book is misleading. She also doesn’t turn out to be one of the aliens controlling humankind from behind the scenes. In a shift from a more innocent time, Clowes’ latest work encloses his character in a grim, brutal world that’s unforgiving of her and the rest of humankind.

‘Monica’ is available at The Escapist comics bookstore at 3090 Claremont Ave. in Berkeley. escapistcomics.com.