In his first year in office, Jerry Brown vowed to make Oakland safer than Walnut Creek. He was just joking, of course. But for his first seven years as mayor, crime rates did drop dramatically compared to the three years before he became mayor: On average, violent crimes and property crimes each plunged by about one-third. The murder rate stayed the same, but overall Brown fulfilled his pledge.

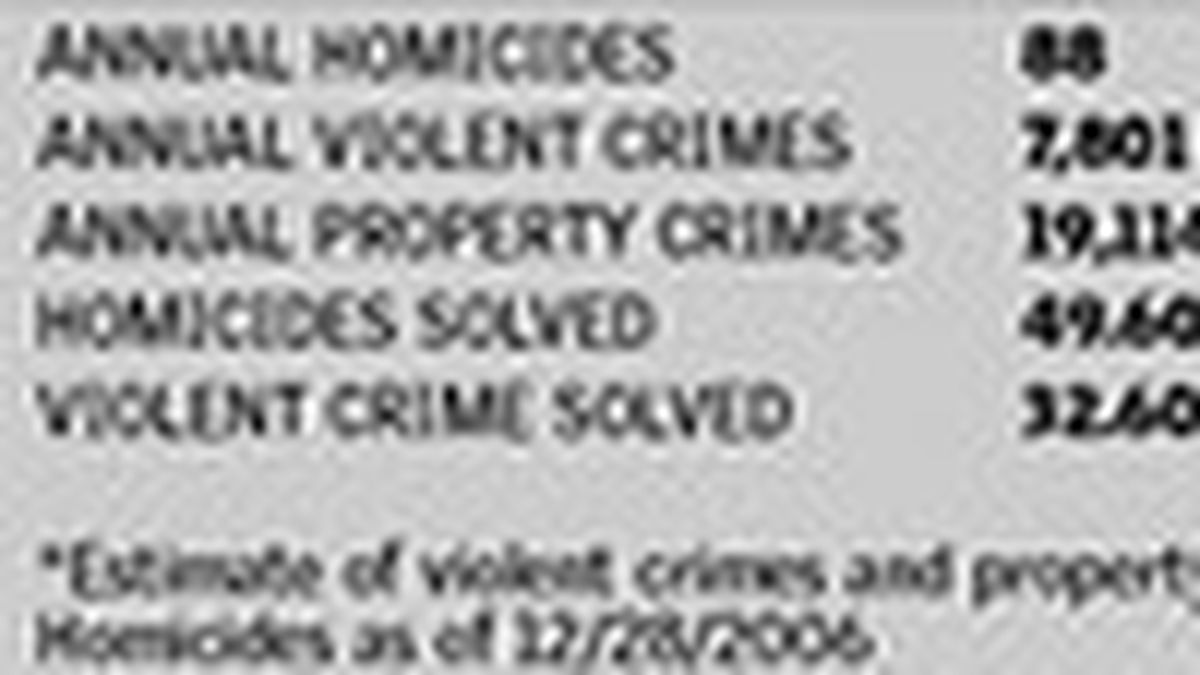

Then came 2006. By the end of the year, Oakland will have recorded about 148 homicides, its most murderous year in more than a decade. Midyear, the city was on pace to suffer double the number of violent crimes it experienced during each of the prior seven years.

This crime spike wasn’t exclusive to Oakland. Other cities in the Bay Area (such as Richmond) and the country (Milwaukee, St. Louis) have suffered similar crime waves. In general, last year’s spike threw into question whether any mayor can really do much to reduce violent crime. More specifically, the increased bloodshed challenged the efficacy of Brown’s many crime-fighting measures in previous years. Most of them were the get-tough type, such as his curfew on parolees. But he also pushed for social-service programs such as Project Choice, which helps parolees adjust to life outside prison.

Alameda County Sheriff Charlie Plummer, who retires this week after twenty years in office, belongs to the school of thought that says a mayor or even a police department has little, if any, impact upon crime. It’s the people in a community who actually affect crime rates. “If you have low-class people living in your town, you’re going to have crime,” the tough-talking sheriff said. To back up his point, he posed a rhetorical question: Do you really think that Oakland’s police department is worse than that of Piedmont?

Brown, however, refuses to believe that a mayor and his police department can’t make an impact. He points to Rudy Giuliani’s success cleaning up New York. “I think I’ve made a major impact in Oakland,” he boasted. “I’ve moved mountains. … I mean, everything is a fight.”

He’s right about that. For instance, Brown’s first attempt in 2002 to get voters to raise taxes to hire a hundred more cops failed. Two years later, he was forced to settle for a more modest package authorizing 63 more cops and a smorgasbord of social programs. Most recently, he has quietly battled behind the scenes to persuade recalcitrant superior court judges to increase bails for illegal gun-possession crimes.

District Attorney Tom Orloff, who has been a prosecutor in Alameda County for more than thirty years, credits Brown for his persistence. “I don’t think there’s been a mayor who has been more engaged and more supportive of the police,” Orloff said.

But Brown’s keen interest in policing sometimes created resentment among cops who thought that he was meddling in counterproductive ways.

Former Deputy Chief Michael Holland, who retired in December 2005, grumbles about one edict from Brown that required the department to form a joint task force with the Drug Enforcement Agency. Holland said the DEA had first asked the police directly, but the brass shot down the plan because they felt the department couldn’t afford it. Then the DEA sold Brown on the idea, and all of a sudden Police Chief Richard Word, who owed his job to the mayor, ordered Holland to reassign his gang unit to the DEA task force. Doing so gutted the gang unit, Holland griped.

Holland said that while the task force made some nice drug busts, the city saw an influx of gang violence around the same time. “You can’t always rob Peter to pay Paul and not expect there to be a fallout,” he said.

As Brown leaves, the department is in bad shape. Although he eventually got voters to approve the hiring of more cops, the department remains horribly understaffed due to attrition, slow recruiting, and an earlier hiring freeze. The force is down 115 cops from the 803 officers authorized in its budget.

The mayor also presided over the department during Oakland’s biggest police scandal in decades: the Riders, four rogue West Oakland cops who allegedly beat up and framed dozens of mostly African Americans in the late ’90s and 2000. The district attorney wound up dismissing more than seventy drug cases that were tainted by the Riders.

Two separate juries acquitted three of the Riders on some of the criminal charges, but deadlocked on the rest, resulting in mistrials. (The fourth fled the country before he could be arrested.) Interestingly, the rogue cops’ lawyers laid much of the blame at the feet of Jerry Brown, whom they accused of creating a mandate to do whatever it took to get the crime numbers down. Years before the acquittal, the city agreed to a $10.9 million settlement with alleged Riders victims. As part of the settlement, a federal judge will monitor the department until at least 2008.

The internal affairs division has tripled in size since presettlement days, Captain Ben Fairow said. And while there are 27 sworn officers in internal affairs, homicide has only 14. A November report by KTVU Channel 2 suggested that cops have grown afraid of being proactive for fear of subjecting themselves to bogus complaints and internal-affairs investigations. Brown also views the consent decree as a burden on efforts to fight crime in the city. “It’s made policing the police the top priority — not the criminals,” he said.

Even as Brown prepared to become California’s next attorney general, he was still preoccupied with the struggle to fight crime in Oakland. In his final weeks as mayor, he hired a consultant recommended by former New York Police Chief William Bratton to evaluate Oakland’s police department. Brown said he hopes the report, scheduled to be finished before he leaves office, will serve as a blueprint for incoming Mayor Ron Dellums.

In the meantime, Brown won’t be far away should Dellums want more advice. Instead of moving to the state capital, he will work from Oakland and continue living with his wife in their apartment at 27th Street and Telegraph Avenue, a crime-ridden downtown area where eight people have been murdered since he moved in three years ago. Brown said he’s sticking around to finish what he started and get a handle on the city’s violent crime rate. Maybe he’ll have more success as attorney general than he did as mayor. But probably not.