What makes Xavier Dphrepaulezz, aka Fantastic Negrito, a changemaker?

Consider the following: He has won three consecutive Grammy awards for Best Contemporary Blues Album – as an independent artist. Unlike some modern-day artists working in the blues idiom with a distinct retro approach – Gary Clark, Jr. comes to mind – Negrito’s music, which he also produces in addition to songwriting and being the featured vocalist, has consistently pushed the envelope with social commentary. He has expanded his business model in innovative new directions by founding his own record label, located in an unglamorous strip of West Oakland concrete, which has served as an community-gathering event space. His new offering, White Jesus Black Problems, doesn’t just stoke controversy with its provocative title; it’s a concept album based on a true story of forbidden love – which he has turned into an Afrosurrealist film destined to become a cult classic.

Much of the Fantastic Negrito backstory has become the stuff of urban legend: how he ran away from home, ran the streets of Oakland and Berkeley as a teenager, and moved to Los Angeles to escape street violence. How he was signed to a major label as a hip-hop artist, but ended up being a drug dealer instead. How a near-fatal car accident left him in a coma. How he recovered and reinvented himself as an artist, busking at BART stations. How he won NPR’s “Tiny Desk” competition, catapulting him to critical acclaim and international tours. How his music and appearance—most of his outfits are thrift-store finds—are unconventional, eclectic and stylistically brilliant. What remains to be told is a final chapter, where Fantastic Negrito’s epic journey concludes with his most ambitiously creative effort yet.

One Friday evening in early June, Dphrepaulezz held court at Oakland’s New Parkway Theater. The audience has just watched a screening of the film version of White Jesus Black Problems. It’s a lot to take in, especially upon first viewing. The film is loosely set during a time when the Southern economy relied on the labor of both African slaves and European indentured servants. The plotline follows the romance between two such individuals—Dphrepaulezz’s relatives—who become intimate, despite their romance being completely taboo.

The film opens in present-day Oakland, where Black children jump rope and play hopscotch. A Black girl plays with a white doll; as archival images of a Black man and a white woman are juxtaposed, Dphrepaulezz’s voiceover is heard: “the most important thing is that, all people are born free.”

A surreal sequence follows: A silver sequined spirit emerges from some ethereal dimension and traipses down West Oakland’s concrete sidewalks. The visuals cut between a white woman in a rose garden, and a Black man in a forest playing a drum. Equally ethereal, psychedelic music plays, reminiscent of early Pink Floyd—if Pink Floyd had gospel influences. It’s all very idyllic—until unseen hands place a hood over the Black man’s head, forcing him into captivity.

Later on, Negrito and his bandmates are shown playing modern instruments in natural settings. Placing electronic keyboards and guitars within the antebellum South speaks to the transformative catharsis the movie—and music—aims for. So does a scene showing an African priest—played by Dphrepaulezz—leading a religious ritual overflowing with spiritual juju.

White Jesus is never depicted. The titular reference euphemizes a mentality that allows for oppression and inhumanity, in the name of religion. There’s a scene where Carol Dutra, Storefront’s kind-hearted, blonde-haired accountant, personifies that oppression in a xenophobic diatribe (playing that role, Dutra says, made her cry afterwards).

During a Q&A session, Dphrepaulezz explains that the film—shot in various Oakland and East Bay locations, with an all-Oakland cast—happened as a response to the ennui of sheltering in place. The central relationship is part of his family’s secret history, revealed after finding documents proving the existence of what he calls a “revolutionary love story.”

That revelation had personal reverberations for him.

“I discovered that I’m not who I thought I was,” he later explained. “My last name was completely made up. My father was not from Somalia. He was from the Bahamas, a hundred percent Caribbean.” The person he called his grandfather his entire life wasn’t actually his grandfather. And, “I found that my dad had another family.”

The evening closed with Dphrepaulezz performing a short acoustic set on guitar. The naked setting allowed him to show off the finesse of his vocal timbre, from resonant tenor to Prince-like falsetto. Watching from the wings, I couldn’t help but think how masterful of a vocalist he’s become since Last Days of Oakland was released in 2015. He expertly uses his voice as both an instrument and a vehicle for social commentary and uplifting messages.

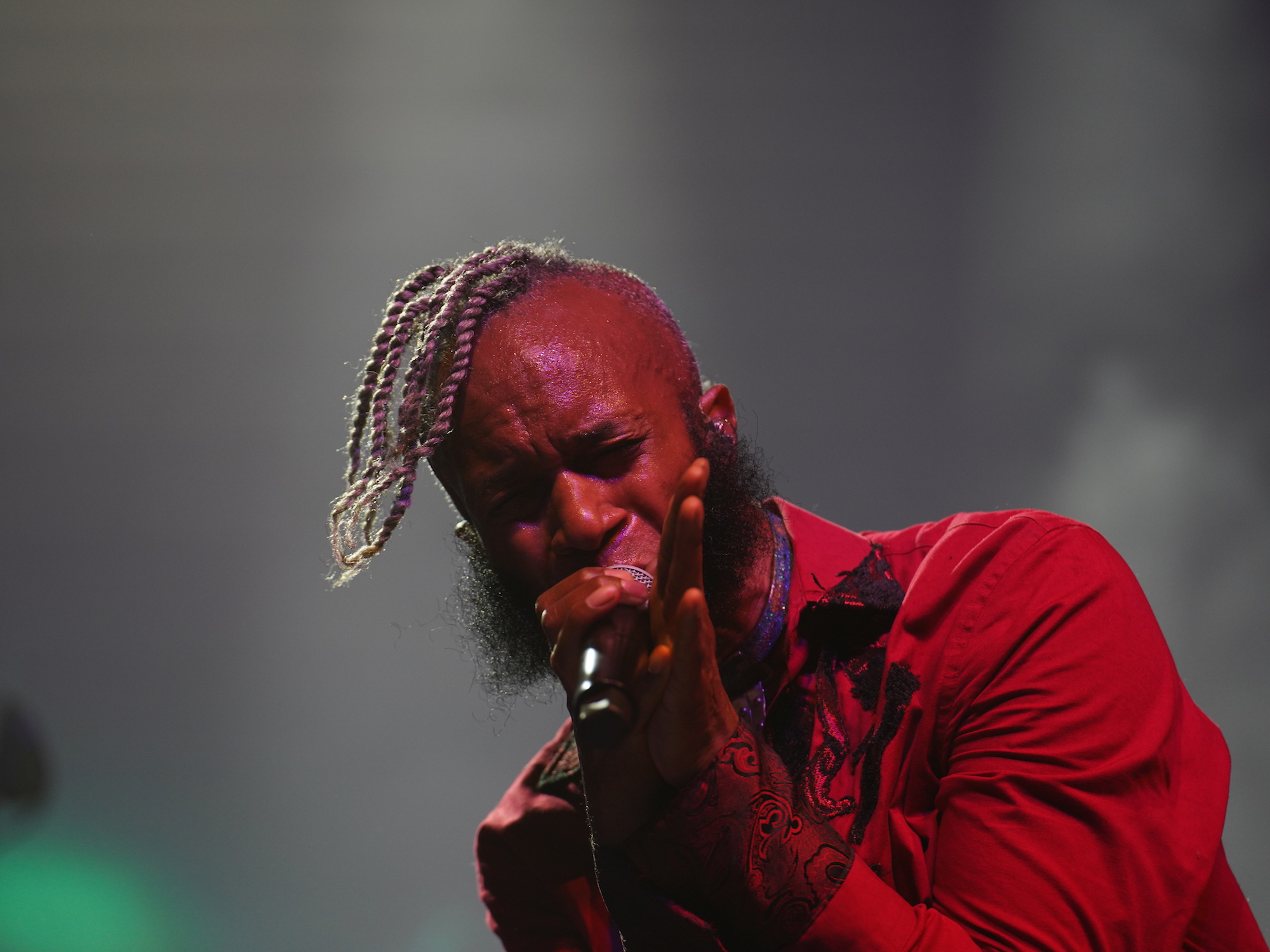

The following night, Fantastic Negrito played a show at Berkeley’s UC Theater. His band is totally dialed in; as a frontman, it’s impossible to take your eyes off of him. The evening’s big takeaway is how seamlessly the new songs blend in with older material like “Night Has Turned To Day.” Along with the ongoing observation that rock, funk and soul-based music still sound amazing live, in a post-hip-hop world.

A few days later, I met up with Dphrepaulezz at Storefront Records. The record label is located next to the California Hotel, an historic venue built in 1929 that once hosted James Brown, Mahalia Jackson and Big Mama Thornton. Storefront looks fairly nondescript from the outside, save for a sign announcing the label’s name. Outside, there’s a parking lot that has served as an event space. Inside, there’s a small studio with mixers, monitors and a vocal mic on a stand.

This is Dphrepaulezz’ creative lair, where he records vocals and sequences tracks. A hallway connects the studio to a larger room where drums are recorded, which also serves as Storefront’s office. I recognize another door off the hallway, from a film sequence where a tracking shot reveals a host of colorfully-dressed characters, revealed one by one. The entire set-up is adorned by colorful pieces of visual art and esoteric curios and bathed in soft amber lighting.

In the main studio, an upright wooden piano’s vintage look is offset by the placing of Fantastic Negrito’s catalog on its mantel. There’s Last Days of Oakland, 2017’s Please Don’t Be Dead, 2020’s Have You Lost Your Mind Yet? and White Jesus Black Problems, all issued as vinyl records.

The four albums signify an uncompromising artistic vision that seemingly encapsulates the entire history of Black music while remaining contemporary and relevant. Each successive release has resulted in deeper and more resonant artistic statements.

Dphrepaulezz—who’s in his early 50s—feels his main obligation as an artist is to his children. “Every album I make, I’m really talking to them. If they could never hear me as a person, as a father, if something happened to me, I’m talking to them. But every album (also) has a theme.”

Last Days of Oakland introduced the character of Negrito, a reformed narcissist with a bird’s eye view of how gentrification was reshaping his hometown. Please Don’t Be Dead expanded the social and political commentary and the musical palette; the single “The Dufller” conjured ’80s Prince jamming with ’70s Al Green, from the perspective of a newly-homeless person. Have You Lost Your Mind Yet? upped the funk quotient, recalling Sly Stone’s peak, and dipping into flavorful collaborations with Tank and the Bangas and E-40, all the while addressing mental health. It all worked, sometimes ironically so. (As one YouTube commenter remarked, “this is insanely GREAT!”)

White Jesus Black Problems’ themes include “challenges, courage, contrast, audacity revolution and love, all in a soup,” he says. “And freedom. Let’s not forget freedom.”

The album’s 13 songs (including several interludes) feel like 30. The busy arrangements incorporate a multitude of musical ideas, with constantly shifting rhythmic terrain. The Floydian intro of “Venomous Dogma” segues into field hollers, then vamps into an insistently pulsing rhythm that gradually intensifies. “Nibbadip” opens with an oscillating synth riff that settles into an old-school rock cadence with doo-wop choruses. “You Better Have A Gun” slides into country-folk territory, while “Trudoo”’s yodel-like vocals maintain the rural cowboy trappings. “Virginia Soil” sees a slight return of slide guitar and a gospel chorus repeating “freedom will come.”

Musical moods swing from lighthearted to heavy to abstract, conveying the weight of confinement, the desire of attraction and the paradoxes of the American South. It’s wide-ranging yet rooted, making each new excursion a variation of, and not a departure from, a bedrock aesthetic.

Dphrepaulezz once told me he stays in communication with his ancestors. At the time, he was unaware of the existence of the interracial couple who would inspire his next project. On WJBP, his ancestors are the centerpiece of a fable which holds lessons for today’s racially-divided society.

Dphrepaulezz recalls how researching his family history greatly impacted him. “As I get to the seventh generation, I come across a document that says, Elizabeth Gallimore presented in Amelia County court in 1759 for unlawfully cohabitating with a Negro slave belonging to Henry Jones and having several mulatto children.” He recalls trying to make sense of it all, “and then I thought, white Jesus, Black problems. And now, love comes in.” In today’s society, he adds, “We think we’re dealing with some shit, but can you imagine the day they must have confronted my seventh-generation grandfather for impregnating a white woman?

“This is a story of people who came from two different places. Two different ends of the spectrum at the peak of white supremacy. When the racial segregation laws were as prevalent and as powerful and as deep as they could be. These two people—a Black enslaved man and a white indentured servant from Scotland—chipped away at the edifice of white supremacy. It’s powerful medicine, brother.”

Making the album, he says, made it easier for him to relate to white people. “I know that sounds crazy. But I think I’ve viewed white people as they’re over here and I’m over here. I didn’t know that a white woman with all of her privilege chose freely to love my Black enslaved grandfather in the 1750s. That’s emotional to me. That digs deep inside of me. And I’m like, man, maybe we’re distracted by this whole (race) thing.”

WJBP is the first full-length release on Storefront, and possibly the last Fantastic Negrito album. Currently touring Asia and Japan, he plans to release a remix album with trap beats, as well as an all-acoustic version. He imagines himself playing shows with just a guitar. But he also feels like he has accomplished what he set out to do as Fantastic Negrito.

“Let’s get Fantastic Negrito out of the way. Let’s go out big. Let’s do a film, full length album, acoustic album and a beat trap mix album, all on White Jesus Black Problems.” His next project, he says, may be a mixtape or compilation of Americana and blues “where I’m not on it at all.”

The future vision for Storefront involves “finding people like myself or like my ancestors, people that won’t take no for an answer, (who are) not afraid to be original and work hard.” Being part of the community is also important. “I wanted it to be a label that was accessible and that provided and contributed something right here on 34th and San Pablo.”

To that end, “I created a market—which people thought was strange for a label—but I created an outdoor market called Storefront Market, where there’s a stage where people can perform and there were vendors and there was no fee for the vendors; whatever they made, they took it home that day.”

Xavier Dphrepaulezz is a changemaker who first had to change himself before changing the world. He has changed how people think about Black music and blues in particular. He has added to the legacy of independent labels and independent-minded artists from the Bay Area. The success he has enjoyed has largely been on his own terms; he has rejected convention and embraced individuality.

“There was a lot of me growing up in the Bay Area, feeling like an outsider, feeling like a rebel, feeling like I couldn’t fit in. I wanted to get in so bad, but I could never get in. And then I found out that I didn’t want to get in, and I would make my life about that.”