Americans can be excused, in this anxious year, for seeking out a certain brand of movie escapism — not necessarily a mindless comedy or grotesque fantasy, but something to, ahem, make us feel better about each other and our place in the world. (There, we said it.) Feel-gooders are usually one of the most despised of all genres and rightly so, because of their tendency toward easy, maudlin, push-button touchy-feeliness. But sometimes, when they sneak up on us in another guise, reassuring dramas and soothing documentaries — those are very rare — can send us out the door in an altered mood with no lasting harm done.

Such a pair of entertainments are Morgan Spurlock’s Where in the World Is Osama bin Laden? and Tom McCarthy’s The Visitor, two films that shrink the world situation to fit the mood of America, and get away with it. Candy-coated reality? Yankee vanity? Maybe so. But their sunniness is welcome.

Spurlock, of course, is the creator of the too-cute Super Size Me, in which he cheerfully bulked up on junk food to prove its harmful effects, and he had a hand in such lightweight Michael-Moore-influenced documentaries as What Would Jesus Buy?, the chronicle of an anti-consumerist guerrilla theater troupe. After a typically spurious Spurlock intro and a video-game credit sequence, the bin Laden documentary opens with the filmmaker’s announcement that he’s going on a road trip to find the elusive terrorist bogeyman, to succeed where the all-consuming “war on terror” has failed. We fear the worst, and indeed there are a few trailer-worthy laff shots such as Spurlock peering into a Tora Bora cave (“Yoo-hoo? Osama?”). But the film grows into something more.

Spurlock & Co. decide to crisscross North Africa and the Middle East, not merely to “seek out” bin Laden but to talk to ordinary people and ask them their opinions of Bush (not surprisingly, they despise him), America (“We like the American people but not their government”), and their own countries, in addition to the film’s title question. There are a number of well-researched, serious docs on 9/11, the Iraq war, and America’s role in the Middle East, but not many have sat down with students, shopkeepers, and laborers and listened to them. Spurlock does, and it’s the saving grace of what might have been a tiresome exercise.

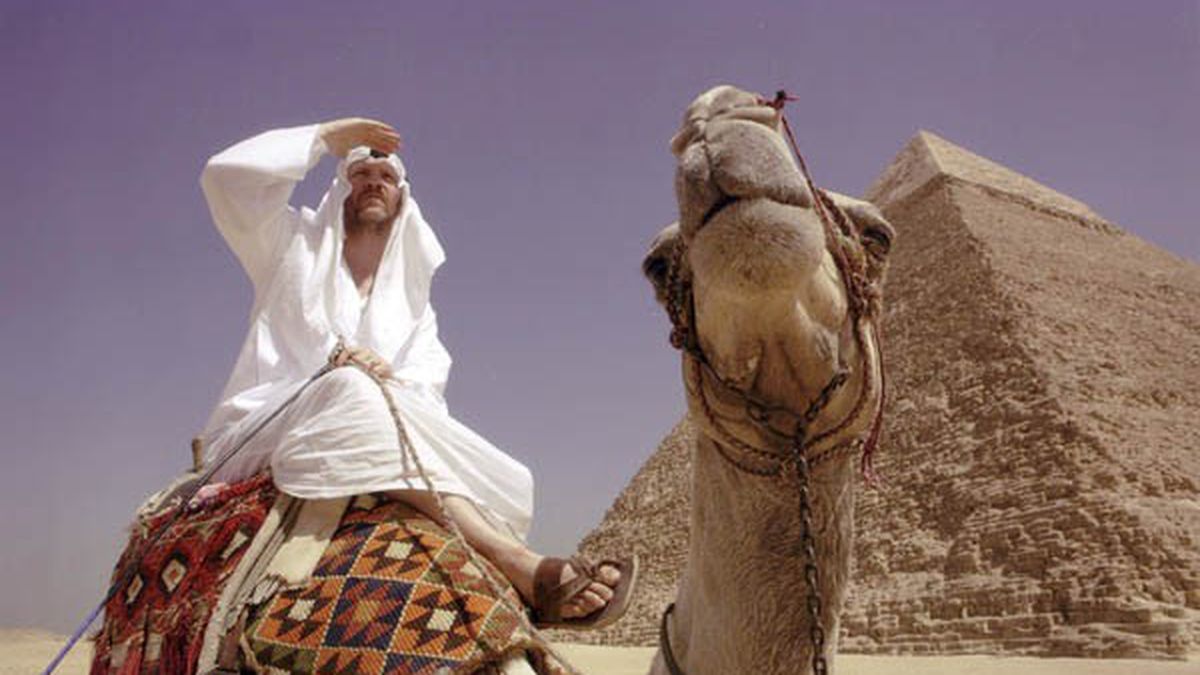

In Egypt, homeland of Ayman al-Zawahiri, Spurlock talks to the Islamic Jihad leader’s uncle, who says he hasn’t seen his notorious nephew lately. With a calm frankness Spurlock finds all over the Mideast region, the old man blames the current troubles on “the seed sown by America.” Spurlock hears a similar refrain everywhere he goes, but there are none of the wild, firearm-waving, frothing crowds so familiar to US sound-bite consumers. Regular Egyptians on the street are concerned but amiable, as are the folks Spurlock importunes in Morocco (where someone cites the need to “create unofficial bridges between civilian societies” instead of relying on governments), Jordan (where the US is seen as an “occupier,” easy to rally against), and the West Bank, where a Hamas member admits his resentment of other Arab nations using the Palestinians and their situation for their own ends.

Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, is obviously a very scary place. Witness the pair of high school boys (never girls) chosen to talk to Spurlock, and their worried glances at the teachers in the room just before the interview is abruptly shut down. Saudis who consented to speak to Spurlock acknowledge that there is zero separation of church and state, and voice hope for some sort of secularism in Saudi society. The Iraq war is spilling over, they tell us. The most hostile reception Spurlock gets, however, is from publicity-shy Hasidic Jews in Jerusalem — he’s practically mugged on the street.

Spurlock wends his way through the ruins of Afghanistan (one old warrior shouts: “Fuck bin Laden! And fuck Bush!”) and even gets himself embedded with a US military unit in the Tribal Area near Pashawar, Pakistan, but he never runs into Osama bin Laden. Maybe he should have checked out Washington Square Park in New York City, where much of the action in The Visitor takes place.

In common with Spurlock, writer-director Tom McCarthy (The Station Agent) is concerned with the notion of the US finding its true role in the world, but his more oblique investigation frames itself as the story of a solitary 62-year-old university professor named Walter Vale (played perfectly by character actor extraordinaire Richard Jenkins) who arrives in his New York pied-à-terre apartment one night to find it occupied by two immigrants.

Zainab, a stunningly beautiful woman from Senegal (portrayed by American-born, Zimbabwe-bred Danai Gurira) and her outgoing Syrian boyfriend Tarek (Los Angeles-based actor Haaz Sleiman) have been conned by a third party into thinking they’re renting the place. The bewildered Walter is about to throw them out, but hesitates and invites them to share his space. Economics prof Walter, the squarest of academic drones, clearly needs some of Tarek and Zainab’s Third World spice, particularly in the African drums Tarek plays in the park while Zainab sells her jewelry in a street stand.

The two men bond over drumming (“Think in threes, Walter”). Tarek treats the older man to a Fela Kuti CD and then a drum. Later, when Tarek runs into trouble, the two men’s camaraderie and respect for each other pays off, and Walter’s awakening continues in the form of Tarek’s mother, Mouna (warmly played by Palestinian actress Hiam Abbass), who arrives from Michigan to help Walter deal with immigration lawyers and other matters he never before considered.

It’s as if the tweedy Connecticut teacher drinks in the world in one long gulp. Jenkins has lent quality support to numerous movies (Flirting with Disaster, Hannah and Her Sisters, There’s Something About Mary, etc.) but The Visitor gives him a chance to develop a character for the whole running time. Walter’s body language speaks volumes — the awkwardness of a lonely old man slowly giving way to the relaxation of true friendship. Halfway through the film, McCarthy’s title suddenly makes sense: It’s not Tarek, Zainab, and Mouna who are the visitors on this planet, it’s Walter, the isolated man who discovers the rest of humanity by accident, the luckiest accident he’s ever had. If there’s hope for Walter, there’s hope for all of us. Even Osama bin Laden.