You run into a man like Paul Aufiero practically every day. He’s the one who bags your groceries, drives you around in his taxi, and sells you popcorn at the movies. You probably don’t pay him any attention. But of course he’s got a life story, like you and everyone else. In Big Fan — the new movie by Robert D. Siegel, who wrote The Wrestler — we spend a few days and nights with Paul, played brilliantly by comedian Patton Oswalt, just to see what makes him tick, and we get more than we bargained for.

In the 1993 drama A Bronx Tale, there’s a scene in which the local gangster, played by Chazz Palminteri (who wrote the play on which the movie is based), straightens out his young admirer, Calogero, after the kid expresses his undying loyalty to Yankees outfielder Mickey Mantle. “Why are you so devoted to Mantle?” asks Sonny, the Palminteri character. You think if your dad loses his job or you get sick, Mickey Mantle is going to come pay your rent? Mantle doesn’t do anything to deserve your respect, he tells the kid. The lesson sinks in.

Paul Aufiero never saw that movie, and no one explained that particular section of the facts of life to him. And so it is that after spending his evenings “sitting in a box” as a parking-garage attendant, fanatical New York Giants football supporter Paul returns to his bedroom in his mother’s home in Staten Island and faithfully dials up a New York sports talk call-in radio show to sound off about the Giants’ last game, and their next one, all the while verbally sparring with his nemesis, Eagles fan Philadelphia Phil (Michael Rapaport). Paul spends the whole night at work scripting his “spontaneous” comments. After his big moment, he turns off the light and masturbates. If we ever wondered about guys who call into talk radio, Big Fan scratches that itch.

Man-child Paul and his similarly disposed buddy Sal (the always dependable Kevin Corrigan) perform their own sad little ritual for every Giants home game. They drive to the Giants Stadium parking lot and have a tailgate party with the other fans, then hunker down in the car to watch the game on TV — no tickets. That’s about as close as Paul and Sal ever get to their heroes, except for one fateful night when they spot Giants linebacker Quantrell Bishop (played by Jonathan Hamm) at a Staten Island gas station, follow him all the way to a Manhattan nightclub, then awkwardly approach the oblivious athlete and his lounging pals to declare their devotion. Things go wrong quickly, then a bit more slowly, then very quickly indeed for Paul from that moment on.

Screenwriter Siegel, directing his first film — he previously edited The Onion — lavishes as much attention on forty-year-old virgin Paul as he did on “Randy the Ram” in The Wrestler, following him home, holding a shot just a few seconds longer to capture the seemingly insignificant gesture that explains a personality. But there’s always a problem ending this sort of film, because getting a character like Paul into a jam is far easier than providing with a redemptive way out.

Paul Schrader and Martin Scorsese, for instance, redeemed Travis Bickle in a montage at the end of Taxi Driver — that is, they imposed redemption on him from above. Something similar happens to Paul Aufiero, and it leaves us feeling slightly betrayed, but only slightly. Never mind Paul’s Taxi Driver-style habit of adding sugar to his Coca-Cola.

TV veteran Oswalt, who performed at any number of Bay Area comedy clubs during his stand-up career, inhabits the lumpen Paul thoroughly, from his poster-decked juvenile bedroom to his bickering bouts with his mother — à la fellow loner with a boner Rupert Pupkin, still another Scorsese touchstone. And while we’re on the subject, is there any actor other than Corrigan who can lend such instant, unerring authenticity to a New York working-class character? All he has to do is show his face. Also good: Gino Cafarelli and Serafina Fiore as Paul’s shyster-lawyer brother and bizarrely statuesque sister-in-law. So what if, in the end, Paul Aufiero is simply not as compelling as Randy the Ram? The world needs parking lot attendants just as much as pro wrestlers.

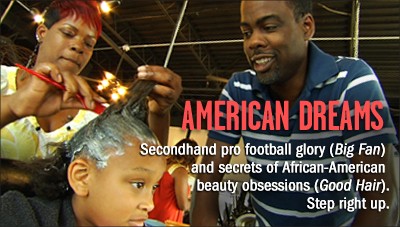

Who would have thought that Chris Rock would make one of the best documentaries of 2009? Comedian/interviewer/writer Rock, along with four other writers, including director Jeff Stilson, is the chief perpetrator of Good Hair, a wildly entertaining cultural commentary and business story about a $9-billion-a-year industry that seemingly only black people and beauty professionals know about — hair products for African-American hair.

With wise-cracking Rock in the lead like a welterweight Michael Moore, we learn about things every black person in the US deals with on a daily basis: the role of hair relaxer as a nappy antidote; the “creamy crack” addictiveness of it for silky-smooth coifs from Prince to Nia Long to Michelle Obama; the wide world of weaves; and the multimillion-dollar “secret” route of human-hair extensions from Hindu temples in Chennai, India, to the salons of Los Angeles, weave capital of the world.

Relaxer, as any old-school conk-rag hepcat knows, burns like hell. It’s made of sodium hydroxide in factories like the Dudley Manufacturing Co. of Greensboro, North Carolina, one the very few black-owned companies that sell to this huge market. As one talking head notes, 12 percent of the population buys 80 percent of the hair products, and the entire concept of treating nappy hair to create fake “silkiness” is barbed with questions of race, cultural domination, slavishness to fashion, and other touchy subjects. Rock gleefully pricks open the wounds.

Hair weaving is a laborious, often painful operation in which human hair — obtained by the ton from places like India and Malaysia — is attached to the scalp to achieve the ultimate “white hair” effect, like the late Farrah Fawcett, for customers who pay $1,000 and up (wa-aaay up) and spend six to eight hours on the treatment. Rock talks to the husbands and boyfriends, sitting waiting for their women, and their sheepish grins tell the story. Got to have it, no matter what the price. One of the film’s expert witnesses, the processed Rev. Al Sharpton, puts it succinctly: “They wear their economic exploitation on their heads for all to see.” America has a long way to go before it can finally cross the racial divide, but movies like this hilariously ironic documentary are a step in the right direction. Let it all hang out.