When asked which East Bay city would be a fitting analogue for their Panamanian homeland, emcees Rico and Dun Dun snickered. “You went to North Richmond?” asked Dun Dun. “It’s like North Richmond. It’s fucked up, I mean, but North Richmond is still cool. That’s the closest.” Dun Dun grew up in Veranillo, Panama, where he lived with an aunt and several sisters. His cousin Rico hails from Panama Viejo, an old colonial city located on the outskirts of the nation’s capital. The two have similar backgrounds: Both lived with iron-fisted aunties who tried to mold them into good folkloric musicians. Both immigrated to the United States as teenagers, and wound up in East Oakland. Both turned to hip-hop as a way to purge their anxieties and their longing for home. Both became enamored of Top 40 rattle-and-clap beats, but also retained their love for son clave rhythms and Caribbean dancehall. Until a couple years ago, neither realized this whole collusion of circumstances could yield a viable art form.

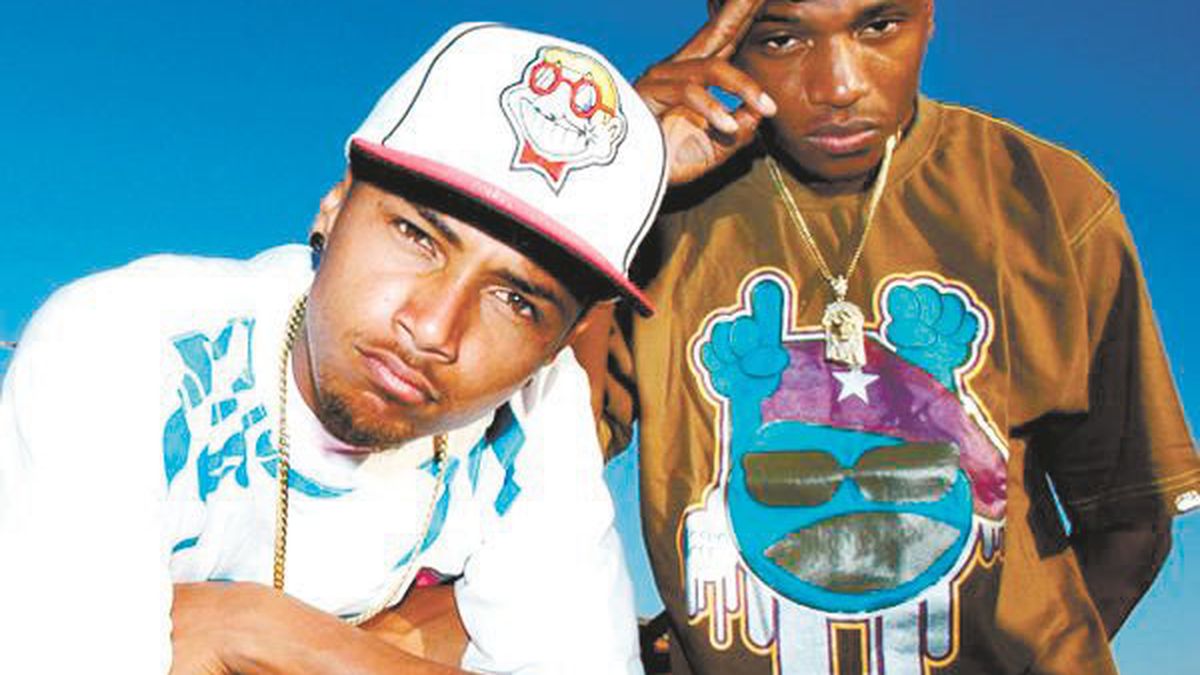

Rico is small and wiry, with neck chains and a black beanie. At 22 he has the look of a kid who just got away with something — the majority of Rico’s stories begin with the line “Man, I was kissing this girl, right? … Nah, I’m just playin.'” Dun Dun, who used to call himself “Panama,” but changed his name after traveling back home a couple years ago (his new, subtler alias derives from a Panamanian folk character who flogs people’s rivals in exchange for bribes) is tall, dark, and speaks with a thick Spanish accent despite six years spent living in East Oakland. He wears airbrushed baseball caps and has the word “Respecto” tattooed on his left hand. Dun Dun’s a bit of a ham; Rico’s an unrelenting flirt; they’ve both realized the importance of taking a persona and inhabiting it. “We’re like cappuccino and espresso,” Rico teased.

Rico and Dun Dun didn’t gravitate to music on their own; rather, music was foisted upon them by an overbearing aunts. Rico’s aunt used to set up variety shows with kids from the neighborhood, and would feature her nephew as a fledgling meringue balladeer. (Somewhere, deep in the bowels of someone’s home video archive, lies a tape of little Rico singing “El Mono Dudoso” — rough translation: “The Doubtful Monkey.”) Dun Dun’s aunt steered him into folkloric típico dance when he was nine years old, much to his embarrassment. “At first I didn’t like it because it was like, ‘that’s not ‘hood,'” he said. “That’s why people were laughing at me. They’d be like, ‘That shit ain’t ‘hood, bruh. Let’s go play soccer.’ I’d be like, ‘Nah, I gotta go practice típico, bruh.”

Now twenty, Dun Dun started rapping as a sophomore at Oakland High. He wanted to emulate dancehall emcees he’d grown up listening to — incomprehensible, high-velocity toasters like Mr. Vegas and Supercat — so his raps sounded like a fusillade: “He got no bars, no nothing, dog,” said Rico. “It was like, you know, giving a kid a gun and being like, ‘Just shoot all the rounds, fuck it.'” Rico played more of an ancillary role at first, a sometime hype man who provided his cousin with a lot of constructive criticism. They performed as “Rico and Panama,” and Rico didn’t immediately cop to the idea of forming a bilingual rap duo. “I did not want to sing in Spanish, dude,” Rico recalled. “I’m a hard-headed dude, man. … And I felt like, ‘Yo, I can do something in English. And eventually, you know, I run into my wall about eighty times. And then I be like, ‘Yo, you know what? What the hell am I doing?'”

Rico’s change of heart came about two years ago, after a particularly successful show in Los Angeles. The crowd’s excitement over their Spanish lyrics, dancehall beats, and identity-affirming politics made him realize that Latin-ness was what distinguished them from other rappers. The emcees rechristened themselves “Los Rakas,” which is Panamanian slang for “people from the ‘hood.” (“Like, ‘You hella ‘raka saca‘ man, ‘I don’t mess with raka sacas,'” Rico explained.). Subsequent trips to New York, Miami, and their Caribbean homeland helped crystallize the duo’s polyglot sensibility. Their lyrics run the gamut from party jams and seductive come-ons to direct provocations — Los Rakas does a remix of Lil’ Wayne’s “A Mili” that reverses the rap’s original sentiment, transforming it from a boast into diatribe about avariciousness and rapacity in hip-hop. Most importantly, the cousins came up with a rap style that employed Spanish intonation — the multi-syllable words and luxuriantly rolled “rs” — in a way that’s aesthetically pleasing, even for listeners who don’t understand the lyrics.

While it is not the first rap group to use Spanish lyrics or foreground Latino identity, Los Rakas stands out for doing it really, really well. The cousin’s background in dancehall and meringue distinguishes them from backpackers like 2Mex and Deuce Eclipse, who are fluent in Spanish but lack Los Rakas’ musical depth. (Credit also goes to their roster of local producers, which includes Fly Boy Chapp, Freddy Stylze, and Matt Price.) They sound less contrived than mainstream Latino emcees like Pitbull and Daddy Yankee, who use Miami bass beats and barrio slang more as a way of merchandizing themselves than expressing a cross-cultural sensibility. At the same time, said Dun Dun, coming up in a cutthroat Bay Area market forced Los Rakas to be more innovative and contemporary sounding than their Latin American counterparts. “Spanish hip-hop in Latin America sounds like the hip-hop here in the ’90s, you know?” And we got the privilege of being here.”

Cross-pollinations can be risky, and Rico was right to be skeptical at first, given how easy it is to devolve into ethnic fetishism or get written off as “world music.” Yet the pair has made a go of it by capitalizing on their musical backgrounds and on the romance of the immigrant experience. Three months ago they recruited DJ Ledys, a dreadlocked, Cubana waxslinger who helps give the group a pretty patina. The group’s forthcoming mixtape, La Tanda del Bus, takes its name from the “Diablo Rojo” buses in Panama, which are known for their splashy paintjobs and for the dancehall mixes that bump on their stereos. A follow-up to 2006’s Panabay Twist, it’s a distinctly Latino spin on the “yellow bus” motif that’s been ubiquitous in Bay Area hip-hop. “Every bus has its own mix,” said Rico, who’s now the group’s sloganeer. “We’re gonna have our own route from Panama to the Bay.” As a marketing gimmick it’s well-conceived, but familiar and a little kitschy. It’s what Los Rakas does best.