The end of a marriage isn’t necessarily the end of the world, unless you’re the couple at the center of Mark Jackson’s play Little Erik. For them, the decay of their relationship signals an impending catastrophe that has the power to consume everyone around them — audience included.

The family drama, currently playing at Aurora Theatre (2081 Addison St., Berkeley) until February 28, tackles a slew of weighty themes, from guilt to technological dependence. And Jackson uses his vast experience as a playwright and director to plumb each with the tenacity that has earned him a reputation as one of the Bay Area’s most intelligent auteurs. This time, he has adapted and modernized Henrik Ibsen’s Little Eyolf, one of the least-revived works by the acclaimed Norwegian playwright. And although Jackson’s probing of one of Ibsen’s last pieces occasionally comes up short, it will still manage to transfix the Bay Area audiences that it was undoubtedly updated for.

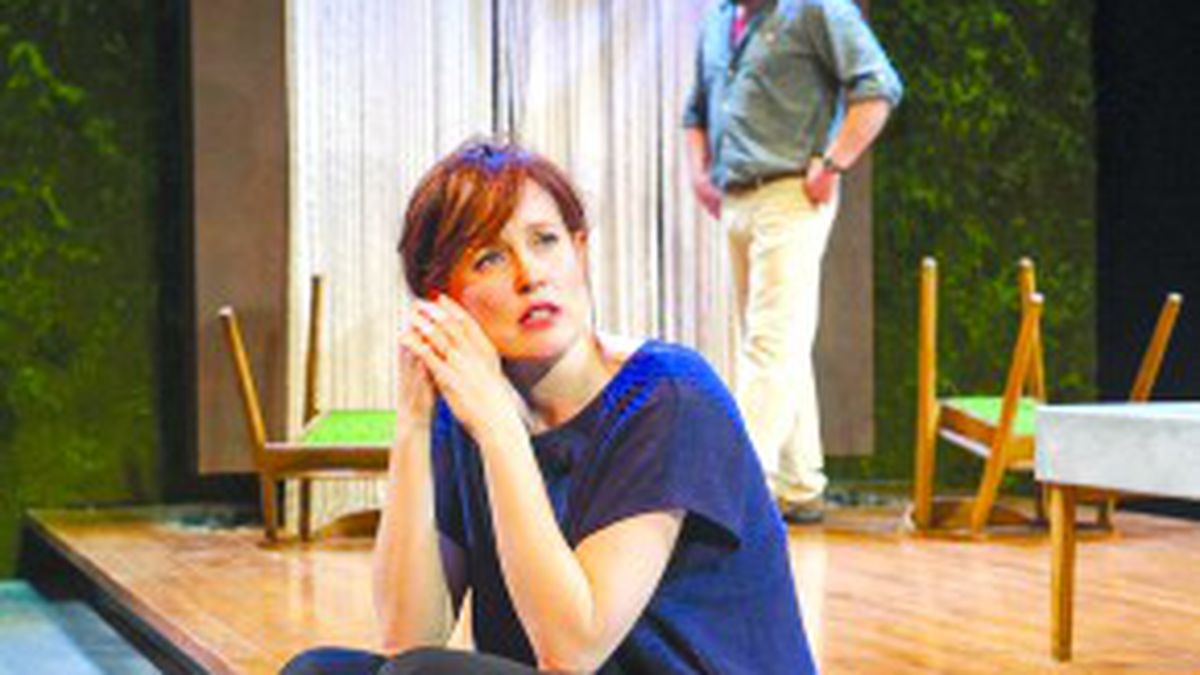

Viewers are first introduced to Joie (Marilee Talkington), an uptight San Francisco tech executive who has been funding her husband’s extended sojourn across the globe. She resents his absence for many reasons, but chiefly because she was left to care for their ailing son, Erik, who broke his spine in a tragic accident. Motherhood was never in Joie’s plans, and she clearly has a more meaningful relationship with her iPhone 6 than the little boy she never really wanted. Her husband, Freddie (Joe Estlack), doesn’t seem authentically interested in Erik, either. He’d much rather hang with his beloved and likeable sister, Andi (Mariah Castle), and talk about their secretive past together. It’s no wonder the fledgling author can’t write his long-planned novel about responsibility. After all, he’s never been forced to assume any, as his wife frequently points out.

The resentment between the married pair is palpable and much more believable than the sexual chemistry that supposedly binds them together. Jackson would like us to believe that Joie is “hard” and Freddie is “soft,” and that the sex between them was once so intense that it alone fueled a happy marriage, but the encounters that are meant to illustrate that tension fall flat. Each character carries deep-rooted contempt for the other, and the play seems sharper and altogether more exciting when it allows them time to revel in that bitterness. Talkington is especially good in those scenes as well; she is unapologetic even when she shouldn’t be and hurls snarky insults with aplomb. Not to be outdone, Estlack brings a steely stoicism as a luddite slacker who would rather absorb the insults than throw them back.

Fortunately, those bitter moments become more frequent as the play continues and another tragic accident occurs: Erik never returns after venturing down to the river near the family’s Northern California-based cabin, and the only person who seems to know what happened — the creepy housekeeper (Wilma Bonet), who has far too few scenes — has disappeared.

The mysterious circumstances surrounding Erik’s death have a devastating ripple effect that’s acutely felt by all who occupy the stage. What follows is a series of explosive reveals that are best left unmentioned here, although it’s safe to note that the play’s inability to create sexual tension in its first half is not repeated in its second. The play largely centers on a series of heated arguments, and these exchanges are most profound when the character’s long-held secrets are tragically exposed.

Surprisingly, however, the most inventive strength of Jackson’s Little Erik lies not in its commentary about anger or betrayal, of which there is plenty. Rather, it’s in the production’s ability to convincingly characterize a Bay Area fueled by a dependency on technology. It’s presumed that Joie works for a successful start-up (she just wants to “connect people virtually”), and every scene is punctuated by the light beaming from the screen of her iPhone. When Erik dies, it’s not her husband she embraces — it’s the Apple device. And she is infuriated that she can’t sync with the cabin’s wifi, but the fact that she shares no connections with the people around her seems of little concern.

Little Erik suggests that this is the future — a world in which our memories are stored in megabytes and familial bonds are considerably weaker than shoddy internet connections. For its fictional characters, the repercussions are literally apocalyptic, and Jackson’s not-so-subtle suggestion is that the digital era may be equally damning for the rest of us.